Antibodies in the European Patent Office – Basic Principles

Over recent years, antibodies have become increasingly important as therapeutic drugs and large numbers of patent applications are filed in this area (>1000 granted by the European Patent Office (EPO) in 2019). Whilst patentability is assessed in the same way as for any other invention, the high volume of cases means that examiners have developed standardised approaches to assessing “antibody-specific” issues. These informal principles have been formalised in a dedicated section of the EPO’s Guidelines for Examination (G, 11, 6).

This briefing provides an introduction to possible claim types for antibody inventions, and also looks at how such claims will be considered by the EPO. The briefing also considers portfolio building to maximise the scope of protection for an antibody invention. We have focussed on therapeutic antibodies, but similar considerations apply to antibodies used in other applications, such as diagnostics.

As will be established below, antibody applications should be carefully drafted in order to maximise the chances of allowance. For more comprehensive advice on the drafting and prosecution of antibody applications please see our related briefing Antibodies in the European Patent Office – Advanced Guide to Drafting and Prosecution, or ask your usual J A Kemp contact. More information can also be found in our regular Review of EPO Antibody Decisions.

Possible claim types Broad claims

The EPO’s standard position is that it is routine for the skilled person to generate an antibody to a known target. Broad antibody claims are therefore increasingly rare, but are still typically available in the following scenarios, in which the invention lies in the target in one way or another:

i. where the target is a newly identified molecule (“An antibody which specifically binds to <target>”);

ii. the target is a molecule to which it has previously proven difficult to raise an antibody (“An antibody which specifically binds to <target>”); or

iii. the target is found to have an unappreciated role in a disease (“An antibody which specifically binds to <target> for use in a method of treating < disease or condition>”.

Nowadays, truly “new” targets are very rare, but may, for example, exist where an applicant has identified a new polypeptide. In scenario (i) it is not typically necessary to provide evidence that an antibody has actually been produced as long as the target is susceptible to routine methods of antibody production.

In scenario (ii), the target is effectively considered as “new”. In this case, the patent application will need to include clear evidence that an antibody to the target has actually been raised, as well as sufficient information to allow further antibodies binding the target to be generated.

Scenario (iii) covers any antibody for use in treating the disease. These claims can be very powerful, especially in situations where few or no other uses than the claimed one(s) can be envisaged, as then the claim is similar in effect to a broad claim to all antibodies to the target per se. In scenario (iii) it will be necessary to establish that the new medical use was not obvious from any previous disclosure regarding the target or existing antibodies that bind to it. It will also be necessary to establish that it is at least plausible that an antibody binding to the target will have a therapeutic effect. Merely showing that the target is expressed during the disease is unlikely to be sufficient and some form of direct evidence showing the target plays a role in the disease mechanism will likely be required. The EPO will generally accept in vitro functional data, particularly if it derives from a disease model or other assay relevant to the indication.

In vivo data from animal models is helpful, but not required, and it is not normally expected that a patent application for this type of invention will include in vivo data from human clinical trials.

In rare cases, it may also be possible to claim a general class of antibodies with a particular functional property (“An antibody which binds specifically to <target> and which has <unexpected functional characteristic(s)>.”). However, as set out in G, II, 6.1.3 of the EPO’s Guidelines, in this scenario it has to be carefully assessed whether the application would allow the skilled person to identify further antibodies having the functional characteristic without an undue burden and whether the functional definition allows the skilled person to clearly determine the limits of the claim.

Antibodies defined by sequence

This is now the more common situation, in which the invention lies not in the target but in the antibody that is going to bind it. For a new antibody to a known antigen, it is usually necessary to define the antibody by sequences.

The EPO’s Guidelines specify that an antibody needs to be defined by the number of CDRs required for its binding (GL, G, II, 6.1.1). However, even though much of the binding specificity of an antibody may lie in the heavy chain, especially in CDR3, claims defining antibodies by less than six CDRs will be rejected unless it is experimentally shown that one or more of the CDRs do not interact with the target epitope or if

the claim concerns a specific antibody format allowing epitope recognition with less than six CDRs. Accordingly, defining an antibody by six CDRs is typically required by the EPO, except in a small number of cases where such data are available or where the antibody format by definition has fewer than six. It is also fairly rare for claims that permit variation in the CDRs to be allowed, though this is in principle possible if it can be shown that some variation can be tolerated and a functional criterion is included to exclude inoperative variations.

By contrast to its approach for small molecule therapeutics, the EPO does not consider that a unique structure can confer inventive step on an antibody to a known target (GL G, II, 6.2). Instead, the EPO has developed a requirement that a new antibody to a known target must demonstrate “an unexpected effect” relative to pre-existing antibodies to the same target (GL G, II, 6.2) if it is to have inventive step. In the past, the closest prior art antibodies may have been non-human or diagnostic antibodies but now the closest prior art to a new therapeutic antibody is frequently another high-affinity human or humanised therapeutic antibody, so inevitably this standard has tended to rise.

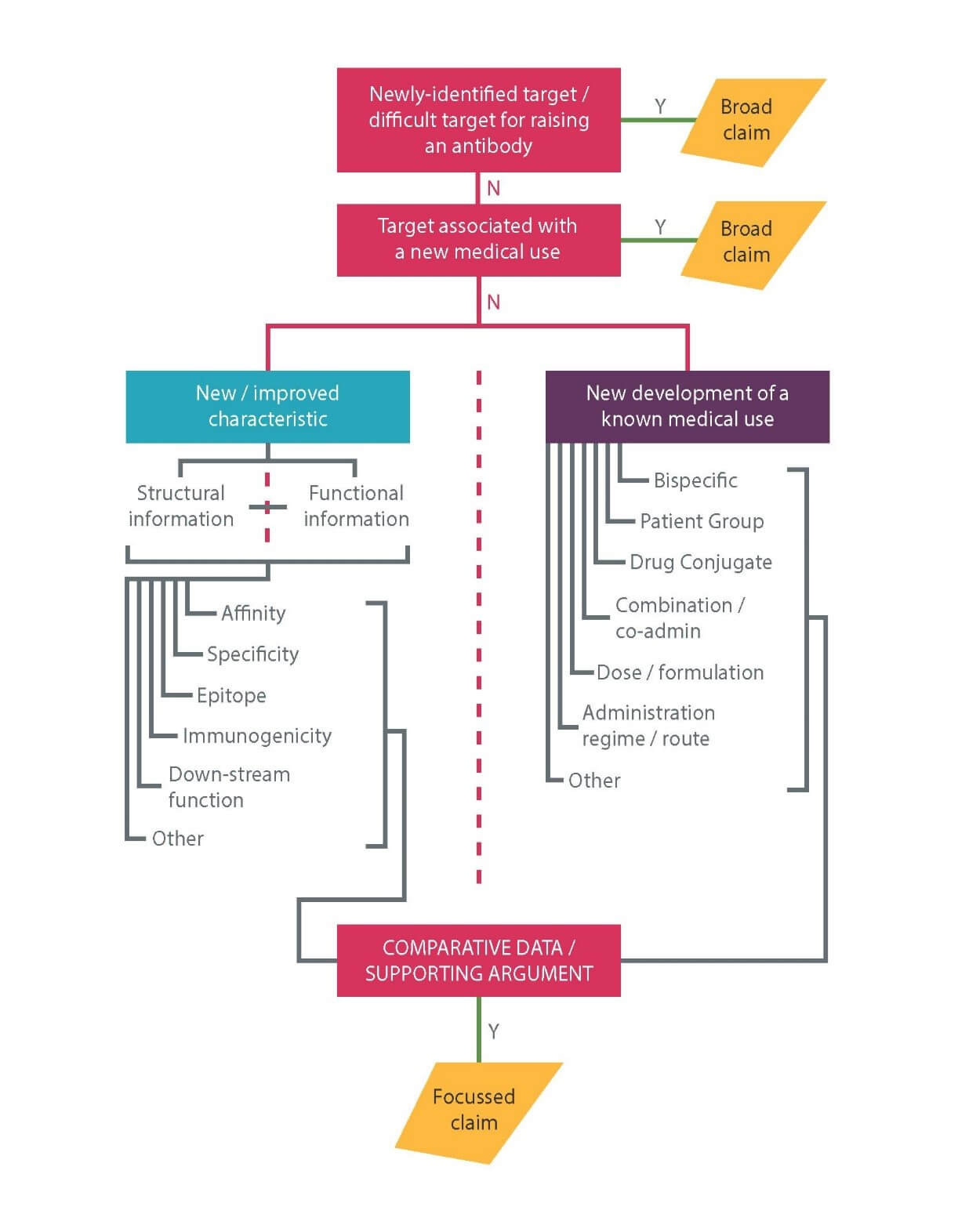

Examples of such effects are described in our Advanced Briefing and shown in Figure 1 below. Importantly, at least some direct experimental evidence of the characteristic(s) relied upon should be provided in the patent application. As long as such evidence exists, supplementary data may then be filed later in support of inventive step.

Once an unexpected effect has been established, the allowable breadth of claim will then depend on whether the effect can be attributed to the CDR sequences alone, or whether the effect is also dependent on the framework regions (or in some cases the isotype of the constant region, or the full heavy and light chains of the antibody). In some instances, a combination of the CDR sequences and a functional definition may be acceptable, provided that the functional definition is considered clear.

Antibodies binding the same epitope as, or competing with, a reference antibody

Claims directed to an antibody binding the same epitope as a reference antibody, or competing with a reference antibody, are frequently used as a means to try and obtain broader protection than sequence-based claims. When prosecuting these claims at the EPO, novelty, inventive step and clarity will be carefully considered. It is in principle possible to obtain broad claims to all antibodies that bind an epitope but in practice this is not easy to achieve.

It will in particular be necessary to persuade the examiner that the invention lies in the epitope itself and not in the sequence of the antibody. Typically, it will be necessary to persuade the examiner that the epitope is effectively a new and non-obvious target. It will also be necessary to establish that all competing antibodies, or antibodies binding to the same epitope, share the inventive property of the reference antibody. In some instances, functional language may be of assistance.

For competition/epitope claims, the application will need to include detailed information on how competition/binding to the same epitope is determined. More information on this is provided in our Advanced Briefing.

Portfolio building

As with any invention, the claim set for an antibody invention should include claims in multiple different categories. Possible claim categories may include polynucleotides encoding the antibody, vectors, host cells, methods of producing the antibody comprising culturing the host cells, pharmaceutical compositions comprising the antibody and medical uses.

A comprehensive filing strategy should also be used in order to enhance the duration of protection. For example, an initial broad filing claiming any antibody binding a new target antigen could be followed up with narrower filings directed to individual antibodies with unexpected improved characteristics. Applications relating to such individual antibodies could be followed up with applications relating to bispecific antibodies, combinations and/or formulations. For a pharmaceutical antibody formulation, the EPO typically takes the position that inventive step can only be acknowledged where an antibody is fully defined as an entire molecule. It is therefore important to include constant as well as variable region sequences.

Similarly, in line with small molecule inventions, broad medical use claims in an earlier application may be supplemented with new applications directed to treatment of particular patient groups, dosage regimes and combination therapies. Claims directed to antibody cocktails for treating infectious diseases are also becoming increasingly common. These possible developments are summarised in figure 1.

In all cases, inventive step is likely to be a key issue and it will be necessary to establish that the development was not obvious from the prior art. This may be achieved via an unexpected improved effect of an individual antibody or, in the rarer case where broader non-sequence based claims are available, via a non- obvious finding regarding the target.

Figure 1