Review of EPO Antibody Decisions January 2018 – January 2021

In our previous discussions of antibody practice at the EPO, we observed that there was a (perhaps surprising) lack of case law to support the evolving practice of the examining divisions. Despite the high number of applications and patents relating to antibodies that have been prosecuted at the EPO more recently (>1000 granted in 2019), the quantity of Board of Appeal decisions concerned with “antibody inventions” remains relatively low. We counted only 21 published decisions in the last 3 years that we considered meet this definition.

Each of the 21 decisions arises from an application with a filing date between 1999 and 2009, which suggests that the Boards of Appeal are continuing to work through a backlog of older cases. Covid-19 will have contributed to the delay in 2020, given that a number of oral proceedings were postponed. The advent of more routine video conference Oral Proceedings may help to redress the balance.

We do not believe that any of these 21 decisions represents a significant shift in EPO practice, or that any of them will compel changes in the way examination is conducted. Instead the picture that emerges is that the EPO largely treats antibody inventions no differently to any other form of technology. In decisions where “antibody-specific” considerations may be applied, the EPO does this consistently and in line with the (now largely established) basic principles that are further explored in our advanced guide to drafting and prosecuting antibody inventions at the EPO. In general, the decisions support the current practices of the examining divisions that we observe in routine prosecution.

Below we give some statistics and discuss the 21 decisions in more detail.

Statistics

We identified 72 decisions published between January 2018 and January 2021 which refer to the term “antibody”. 51 of these decisions were decided on grounds not directly related to the technology (typically Article 123(2) EPC – added matter) and so are not considered further in this review. Of the remaining 21 decisions, 14 concerned appeals from opposition division decisions, and 7 concerned appeals from examining division decisions. 15 of the decisions were issued by Board 3.3.04, 3 were issued by Board 3.3.01, 2 were issued by Board 3.3.07, and 1 was issued by Board 3.3.08. We discerned no obvious differences in practice between the various Boards.

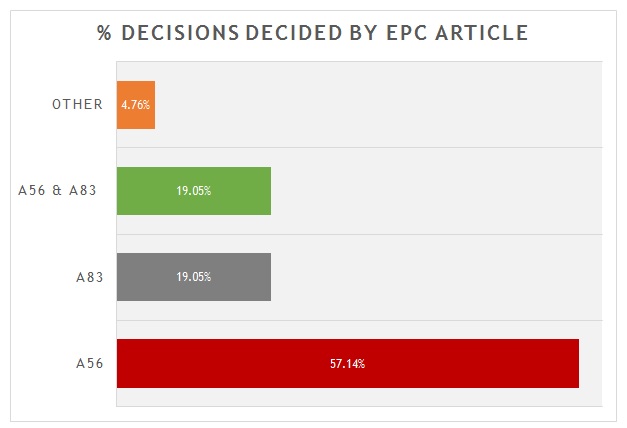

A breakdown of the key grounds for each decision is provided in figure 1.

Figure 1

As is shown, more than 55% were decided primarily on the basis of inventive step (Article 56 EPC). Around 20% were decided primarily on the basis of sufficiency (Article 83 EPC), with another 20% considering both inventive step and sufficiency to some degree. There is often considerable overlap between Article 56 EPC and Article 83 EPC for antibody inventions. Only 1 decision was decided on another ground. In that case the Board found a lack of clarity (Article 84 EPC) in an attempted amendment, with no alternative being offered by the patentee. It is interesting, but not unexpected, that none of the decisions hinged on novelty. Many claims to antibodies recite CDR or heavy/light chain variable sequences that are in practice unique.

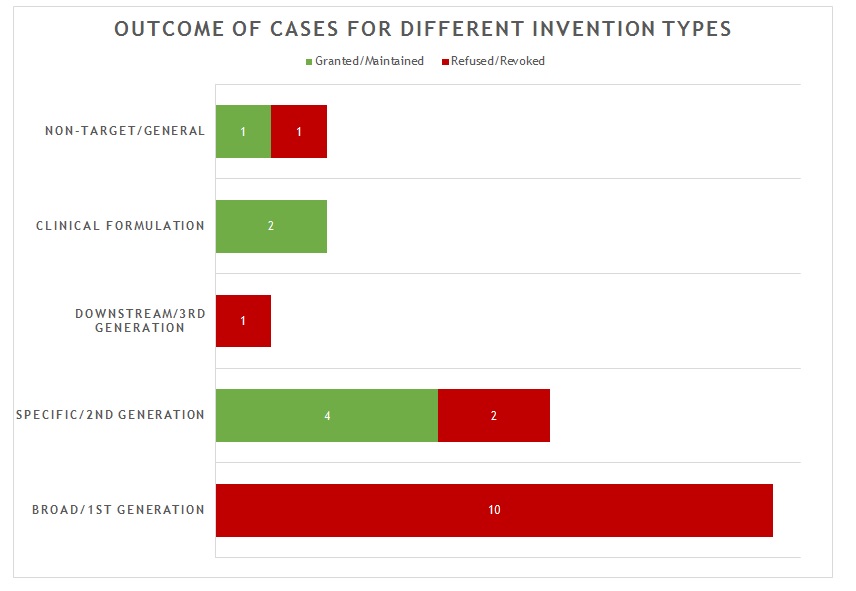

The 21 decisions can also be divided into five general categories of invention as shown in figure 2.

Figure 2

The first and largest category of decision (10 decisions) is concerned with what we define as “broad” or “first generation” antibody inventions. Typically the invention relates to the target and/or a link to a particular indication, rather than to an individual antibody or antibodies. In many of these decisions, no individual antibody was disclosed in the application/patent. The claims instead define the antibody broadly by reference to the target. All of these applications/patents were refused/revoked.

The second category of decision (6 decisions) is concerned with what we defined as “specific” or “second generation” antibody inventions. Typically the invention relates to an individual antibody or antibodies, defined by sequence, and directed to a well-characterised target for which prior art antibodies (often therapeutic antibodies) are known. This is the most common type of antibody invention currently under prosecution at the EPO. Readers are likely familiar with the EPO’s approach to such inventions. Namely that all antibodies specific for a target are obvious by comparison to prior art antibodies for the same target, unless an unexpected effect is plausibly demonstrated. This can be particularly challenging when the prior art includes high-affinity therapeutic antibodies to the same target. In this context, it is not surprising that all 6 decisions in this category featured Article 56 EPC (inventive step) as the key ground. Of the 4 decisions in which the application/patent was allowed/upheld, the claims were limited to focus on individual antibodies and there was a persuasive argument for an unexpected effect. Broader claims were abandoned or never pursued. Of the 2 decisions in which the application/patent was refused/revoked, the arguments for unexpected effect were not found persuasive.

The third category of decision (1 decision) is concerned with what we define as “downstream” or “third generation” antibody inventions. These inventions relate to advances which typically arise during downstream development of a pharmaceutical, such as combinations with other therapeutic agents. In many respects these are not specifically “antibody inventions” and they are usually examined by the EPO in the same way as comparable inventions for non-antibody pharmaceuticals. The only decision in this category was directed to a combination of antibodies to different targets. It was revoked for lack of inventive step following opposition.

The fourth category of decision (2 decisions) is concerned with inventions that are clinical formulations – the active ingredient just happens to be an antibody. In both decisions in this category, the application/patent was allowed/maintained when the claims were limited to a precise formulation of an individual antibody and other listed components, for which an inventive benefit was demonstrated (e.g. stability). This is consistent with examination practice for antibody formulations and is in line with expectations for formulation inventions in general.

The fifth and final category of decision (2 decisions) is concerned with antibody inventions that are “non-target” in nature. That is, the invention is independent of the target of the antibody. Such inventions may relate, for example, to a new Fc domain or a new antibody format. In the 2 decisions in this category, one application/patent was granted/maintained, the other was refused/revoked, both based on the specific facts. In most respects, such inventions are examined in the same way as any other technology at the EPO. There are no “antibody-specific” considerations.

Broad/1st Generation Decisions

T 1095/17 (Anti-LOR-1 antibody for use in treating fibrosis/TECHNION) concerned an antibody target which was known in the common general knowledge to be linked to a particular indication, for which small molecule inhibitors had been shown to be effective. This was enough to satisfy Article 83 EPC and enable a medical use claim specifying the use of an antibody, even though only polyclonal sera were generated in application and were not tested as a treatment. However, the same reasoning essentially rendered the claim obvious as there was in principle no reason why the skilled person would not have seen an antibody as a suitable alternative to the small molecules. There was also some existing evidence that antibodies could inhibit target activity in mammalian tissue.

T 0325/15 (Diagnosis of stroke/BIO-RAD) concerned a diagnostic method using an antibody specific for a different epitope to that disclosed in the prior art. It was refused for lack of inventive step in part because there was no evidence of an associated advantage.

T 0713/15 (Vasculitis/CHUGAI) concerned anti-IL6R for the treatment of vasculitis in general. It was revoked for lack of sufficiency (Article 83 EPC) because although the patent provided evidence of efficacy in 2 patients with specific forms of vasculitis, post-published evidence showed that the treatment was not effective in other forms. A limitation to the specific forms of vasculitis may have been acceptable, but the patentee made this request late in proceedings and discretion to enter it was declined.

T 1872/16 (IL-13 antibodies for the treatment of severe asthma/GLAXO) concerned anti-IL13 for the treatment of severe asthma. There was no link established in the application as filed between the target and the claimed diseases. The medical use claims were held invalid for lack of sufficiency (Article 83 EPC), based on post-published clinical trial data as evidence of serious doubts that anti-IL13 would be a suitable treatment. Antibody per se claims (defined by epitope) were held to be arbitrary/obvious alternatives to known anti-IL13 antibodies.

T 1661/14 (IL-13 antagonists for treating fibroma/GENETICS INSTITUTE) sought to claim IL13 antagonists in general, including any anti-IL13 antibody, for treating fibroma. The causal link between IL13 and fibroma was held to be known in the art, and thus the use of an antagonist in general (including the antibody) was obvious. There was no individual antibody disclosed.

T 1433/14 (Peptide Influenza Vaccine/BOGOCH) claimed particular peptides as viral vaccines, and included also claims to anti-peptide antibodies as anti-viral treatments. There was no credible evidence in the application (actually no data at all) that the peptides were useful as vaccines, and so by extension there was no evidence that the anti-peptide antibodies would be useful as treatments.

T 2321/13 (Hyperproliferative diseases/MAX-PLANCK-GESELLSCHAFT) concerned anti-HER3 antibodies as treatments. Following opposition, the patentee attempted to re-define the disease to be treated solely in functional terms. This was rejected as unclear under Article 84 EPC. No further requests were admitted and so the patent was revoked. A rare decision on grounds other than Article 56 EPC and/or Article 83 EPC!

T 0503/12 (Tumour marker/DIADEXUS) concerned a diagnostic method using an antibody to detect a protein target. The supporting data in the patent concerned only gene/mRNA expression levels of the target. This was held to be insufficient (Article 83 EPC) to support a claim to the method using the antibody, in the absence of protein structure/expression/location data.

T 1389/13 (YKL-40 monoclonal antibodies/BIO-Y) concerned claims to an antibody defined by reference to a particular functional feature. This caused a lethal lack of sufficiency (Article 83 EPC) because no assay disclosed in the application was capable of measuring the feature. The application explicitly described the assays as unable to distinguish between two related phenomena (growth inhibition vs triggering of apoptosis). An attempt to address the problem by removal of the functional feature and focus on binding to a particular epitope failed, because it could not be established that the functional feature was an inherent property of binding to the epitope. Thus this was impermissible broadening after grant (A123(3) EPC).

T 0511/14 (DKK-1 antibodies/MEDIMMUNE) in fact concerns a relatively narrow claim, to a class of antibody defined by 3x light chain CDRs and 1 or more heavy chain CDRs, i.e. only 4 of 6 CDRs defined. However, as is often found with much broader claims in other cases, evidence of superior effects (relative to the prior art) from one exemplary antibody with all 6 CDRs was not good enough to establish inventive step for the entire scope of the claim (Article 56 EPC). The Board also had reservations about sufficiency (Article 83 EPC). Doubts were expressed as to whether even a limitation to all 6 CDRs would cure the problem, since it was not fully-established that the superior property was inherent to the CDRs alone, nor that it been adequately demonstrated (given differences in the assay conditions used for a prior art antibody).

Specific/2nd Generation Decisions

T 0845/19 (Anti-PCSK9 antibodies/AMGEN) was upheld following multi-party opposition, with narrow claims to various individual antibodies defined functionally (“neutralising”) and with 90% or more identity to VH and VL regions or all 6 CDRs. The individual antibodies were inventive under Article 56 EPC. More problematic, broader “competing antibody” claims were abandoned before the appeal Oral Proceedings but would probably have been rejected if they had been pursued.

T 2127/16 (Anti-ADDL antibodies/MERCK) concerned an antibody defined by 6CDRs, with claims also to use in treatment of Alzheimer’s. The advantageous functional feature (inhibition of target binding to hippocampal neurons) was not disclosed or suggested in prior art anti-target antibodies, and evidence suggested it could not be assumed to be an inherent feature of target binding. As such this was held inventive (Article 56 EPC). Post-published data of clinical efficacy was provided, but the Board did not consider it to be necessary. Sufficiency (Article 83 EPC) was satisfied because the evidence in the application itself provided a plausible link between the antibody and treatment effects.

T 2258/15 (PTK7 antibodies/SQUIBB) concerned antibodies defined by specific VH/VL sequences and a functional definition of epitope binding. A functional advantage relied upon for inventive step (enhanced internalisation) was not a feature of the claim, so it was necessary for the patentee to show that it was an inherent property of antibodies as defined in the claim. The Board were not convinced that this was demonstrated, and so the advantage was not taken into account for assessment of inventive step (Article 56 EPC). The antibodies of the claim were then held to be obvious alternatives to known rabbit polyclonal antibodies to same target.

T 1398/14 (Detection of therapeutic antibody/HOFFMANN-LA ROCHE) concerned a method of isolating human/humanised antibodies. It was found to be inventive (Article 56 EPC) when the claims were narrowed to require use of a specific, highly selective, anti-human IgG antibody, even though said antibody was already on public sale. Its high selectivity for human IgG over ape IgG was not previously appreciated.

T 1481/16 (Anti-CD6 monoclonal antibody/CENTRO DE INMUNOLOGIA MOLECULAR) concerned a claim to a specific humanised anti-CD6 antibody for use at a low dose for treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. This was found non-obvious, even though the original murine antibody had been used as such a treatment. The Board found the low dose to be inventive under Article 56 EPC, in the specific context of the case.

T 0605/14 (Anti-angiopoietin-2 antibodies/MEDIMMUNE) concerned a specific anti-ANG2 antibody. The advantage relied upon for inventive step was preferential inhibition of ANG2 versus ANG1. This was disregarded by the Board, because it was held not to be derivable from the application as filed (key evidence in application found unreliable because it literally stated “further experiment needed”). As such, post-filed supporting data was also excluded from consideration of inventive step under Article 56 EPC (the Board also had doubts that the advantage was proven). Absent the alleged advantage, the antibody was held to be an obvious alternative to known antibodies to the same target.

Downstream/3rd Generation Decisions

T 0975/14 (Anti-CD40 and anti-CD20 antibody combination therapy/GENENTECH) concerned a combination of anti-CD40 with anti-CD20 for cancer treatment. This was held to lack an inventive step (Article 56 EPC) over anti-CD40 alone, because the claim encompassed cancers in which anti-CD20 activity would clearly be irrelevant. An attempt to focus on relevant cancers was rejected for added matter (Article 123(2) EPC).

Clinical Formulation Decisions

T 0139/16 (Anti-HER2 antibody formulations/HOFFMANN-LA ROCHE) and T 0159/16 (High Concentration Antibody Formulation/CHUGAI) are similar decisions, in that each concerns a very specific clinical formulation of a particular active ingredient (Herceptin and Actemra, respectively) together with other listed components. In each decision a particular advantage (stability) was demonstrated. In the latter decision, broader claims to any other anti-IL6R antibody in the same formulation were rejected for lack of inventive step (Article 56 EPC), and broader claims which omitted some of the non-active components present in the relevant Example were rejected for added matter (Article 123(2) EPC).

Non-target/General Decisions

T 1856/16 (Antibodies with variant Fc regions/MACROGENICS) was granted with claims to any antibody comprising an Fc region with a specific point mutation leading to enhanced FcgRIIIA binding. The point mutation was considered to be inventive (Article 56 EPC) relative to the Fc sequences then known.

T 0528/18 (Method for producing a stabilised antibody/CHUGAI) concerned a patent comprising a single Example in which substitution of Gly in an Asn-Gly sequence present in a CDR led to improved stability without significant loss of affinity. The claims sought to capture the substitution as a general method of stabilisation applicable to any antibody with a CDR comprising an Asn-Gly sequence. The evidence was considered to be insufficient to support a claim to stabilising any such antibody (Article 83 EPC).

Trends and Conclusions

As evidenced by the revocation or refusal of all 10 of the broad/1st generation cases above, it is increasingly difficult at the EPO to secure and maintain broad, structurally unlimited, antibody claims. At both examination and opposition appeal levels, most successful claims specify at least the 6 CDRs of an antibody and frequently its whole VH and VL regions. This is unlikely to surprise most practitioners, given that it is now relatively rare to identify an entirely new target, or establish an entirely new link between a target and a disease indication.

However, the EPO continues to be consistent when applying its basic principles of antibody examination to the more specific/2nd generation of antibody inventions. Claims to individual antibodies or their uses are allowable, provided there is evidence of an unexpected effect to support a finding of inventive step. Inventions which relate to antibodies, but which are not “antibody inventions” as such, are examined largely the same as in any other technical field. Owing to the time taken for appeals to be decided, the cases reviewed above necessarily relate to applications/patents with relatively early filing dates. However, the approach taken in these decisions matches our experience of ongoing EPO prosecution for more recent applications.