Supplementary Protection Certificates for Medicinal Products

What are SPCs?

A Supplementary Protection Certificate (SPC) is an intellectual property right available for active ingredients of human and veterinary medicinal products requiring marketing authorisation1.

The highest tribunal hearing disputes involving SPCs for EU member states is the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU). Historically there have been numerous referrals to the CJEU on points of law relating to SPCs and this is expected to continue. Some of the key decisions are discussed below.

The SPC regime was introduced as a mechanism to compensate patent holders for loss in effective patent term resulting from the time taken to receive marketing authorisation for such products2. However, regulatory delay is not of itself sufficient to justify the grant of SPCs.

In particular, the relevant regulation provides that an SPC can be granted only for an “active ingredient”. This has been held to exclude substances that may enable or enhance the activity of a therapeutic ingredient, but which have no therapeutic effect of their own on the human or animal body. Despite the clinical testing (and consequent regulatory delay) involved in developing such auxiliary substances, the CJEU has on two occasions3 held that they do not qualify for an SPC. Similarly, it is not currently possible to obtain SPC protection for a medical device, irrespective of whether or not the marketing of such a device has been subject to regulatory delay.

Where are SPCs available?

SPCs are national rights: at present there is no such thing as a Europe-wide SPC. Accordingly, individual applications must be made to national patent offices in countries where SPC protection is desired, although a national SPC application may be based on a European Unitary Patent in those countries in which the Unitary Patent takes effect. Additional information on the Unitary Patent is available here, with a guide to participating member states here.

SPC protection is available in all EU member states, namely:

Austria, Belgium, Bulgaria, Croatia, Cyprus, Czech Republic, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Ireland, Italy, Latvia, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Malta, Netherlands, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Slovak Republic, Slovenia, Spain, and Sweden.

SPCs in these countries are governed by EC Regulation 469/2009 (“the SPC Regulation” – excerpts of which are included as Annex 1).

SPC protection is also available in the following non-EU States:

- United Kingdom: SPCs in the UK are available on effectively the same terms as the EU SPC Regulation, which was transposed into national law at the end of the Brexit implementation period (31 December 2020)4. The EU SPC Regulation continues to apply directly to SPCs which were pending or granted prior to this date. Similarly, CJEU case law prior to this date is applicable, but deviation has become possible. See separate section below.

- Norway and Iceland: these States are members of the European Economic Area (EEA), but not of the EU. However, the governing legislation remains the EU SPC Regulation.

- Switzerland: Swiss SPCs are governed by national legal provisions which are based on the EU SPC Regulation. An SPC issued in Switzerland will also automatically take effect in Liechtenstein5.

- Albania, Bosnia & Herzegovina, Macedonia, and Serbia: These are non-EU/EEA countries which may nonetheless be covered by a European patent application granted by the EPO. SPC protection is available in these countries under national legal provisions.

Similar provisions also exist in neighbouring jurisdictions including Russia and the Ukraine, and in other countries worldwide. Please ask your J A Kemp contact separately regarding rights in these jurisdictions.

What scope of protection is provided by the SPC?

The scope of an SPC is limited to the product of the relevant marketing authorisation. It protects that product to the same extent as the patent on which the SPC is based (“the basic patent”). For example, if the basic patent only covers a method of manufacturing or using the product, then the SPC will be similarly restricted.

Conversely, if the basic patent covers the product per se, the SPC will cover any use of the product which is approved for therapeutic use before the SPC expires. Subsequent marketing authorisations made after grant of an SPC will therefore extend the scope of the SPC, even when the later marketing authorisation is obtained by an entity unconnected with the owner of the SPC. Also, subject to the scope of the basic patent, an SPC will cover all subsequently authorised combinations of active ingredients containing the product6.

The product of the marketing authorisation has long been established to encompass therapeutically equivalent salts and esters of small molecule drugs7, provided of course that they are covered by the basic patent. The situation is less clear for active ingredients which are biological molecules. A decision of the Norwegian Court of Appeal8 following an advisory opinion of the EFTA court9 recognised that it would be desirable for therapeutically equivalent variants of a biologic product to be covered by an SPC, but provided little guidance as to the extent of such coverage. It is to be expected that this question will be referred to the CJEU.

Are there any exceptions from infringement?

The EU/EEA has introduced a so-called “SPC manufacturing waiver” which came into effect on 1 July 2019. It allows manufacture of medicines protected by SPCs for the exclusive purpose of export to markets outside the EEA. Stockpiling for post-expiry use in the EU/EEA is permitted within the final 6 months of the SPC term.

The waiver does not apply to SPCs which were already in force on 1 July 2019. For SPCs which were applied for before 1 July 2019 but which come into force only after that date, the waiver will be applicable but only from 2 July 2022. The waiver will automatically apply to all SPCs applied for after 1 July 2019. An equivalent waiver has been transposed in UK law (see separate section below) and applies to manufacture for export to markets outside the UK and the EEA. No waiver presently exists in Switzerland.

More information is provided in our separate briefing on the manufacturing waiver, available here.

What additional term is provided by the SPC?

An SPC takes effect at the end of the normal expiry term of the basic patent on which it is based, provided that the patent is maintained up to that point.

For EU/EEA member states, the SPC will expire at whichever is the earlier of:

- 15 years from the first Marketing Authorisation in the EU/EEA10

- 5 years from the expiry of the basic patent

The effective maximum term is therefore 5 years in addition to the term of the basic patent.

For non-EU/EEA member states, the term is usually determined by reference to the local marketing authorisation. For example, the term of a Swiss SPC is determined by reference to the date of the Swiss marketing authorisation. Since this can issue later than the EU/EEA authorisation, the Swiss SPC for a medicinal product may have a longer term than the corresponding SPCs in the EU/EEA countries. However, as currently transposed from the EU Regulation, the law in the UK is such that term will be calculated based on the first authorisation for the product in either the EU/EEA or the UK.

It is possible to extend the term of an SPC in the EU/EEA, the UK and Switzerland by a further 6 months by providing clinical results obtained from an agreed paediatric investigation plan (PIP). The PIP must be agreed for the relevant territory / country. The request for extension may be filed at any time up to 2 years before normal SPC expiry. Further information is provided in our briefing note on the Paediatric Products Regulation, available on request.

Additional considerations for the UK post-Brexit

EU law relating to medicines applied in the entire UK until the end of the Brexit implementation period on 31 December 2020. For practical purposes with SPCs, this meant that the EU Regulation continued to operate directly for pending and granted cases filed up to 31 December 2020, including the applicability of paediatric extensions and the manufacturing waiver.

From 1 January 2021 the Withdrawal Agreement was applied, effectively transposing most of the provisions of the EU SPC Regulation into national law meaning that there is (so far) little divergence between the UK and the EU with respect to SPCs, paediatric extensions and the manufacturing waiver. However, there is one important complication. The Northern Ireland Protocol (NIP) to the Withdrawal Agreement provides for EU law relating to medicines to continue to apply directly in Northern Ireland (NI), whereas the transposed UK law applies only to the remainder of the country (Great Britain; GB). This dual regulatory arrangement means that in order to cover the whole territory of the UK under the NIP, a new drug generally requires one MA for GB issued by the UK’s Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Authority (MHRA) and another MA for NI issued by the EMA. For SPCs to cover the whole UK, they must be based upon MAs which collectively cover the whole UK.

This situation will change again when the Windsor Framework provisions relating to medicines enter into force on 1 January 2025, at which point UK law will apply to whole of the UK. SPCs will once again require only a single MA for the whole UK, but this will now be the sole competence of the MHRA. More information regarding the changes between the NIP and WIF can be found in our briefing on the topic available here.

For most applicants it will be sufficient to remember that the UK has recently been subject to three different regulatory regimes for medicines, and that the relevant marketing authorisations for UK SPCs will vary depending on the timing:

- Pre-Brexit: SPC applications filed up to 31 December 2020

Single regulatory regime covering the whole UK = EMA and MHRA

- NIP: SPC applications filed 1 January 2021 – 31 December 2024

Dual regulatory regime: NI = EMA, GB = MHRA

- WF: SPC applications filed 1 January 2025 onwards

Single regulatory regime covering the whole UK = MHRA

In many cases the differences may have a relatively small effect in practice, since the MHRA has indicated that it intends to recognise EMA marketing authorisations unilaterally in the UK for at least two years, post-Brexit. As such it should be possible to file SPC applications in the UK without significant differences compared to the corresponding applications filed in EU/EEA member states.

Furthermore, although examination of SPC applications and grant in the UK will be based on the first authorisation in the UK, the term of the granted SPC will be calculated based on the first authorisation in EU/EEA or UK. In addition, the manufacturing waiver will apply for export outside of the UK and EU, with stockpiling for sale in UK or EU permitted within the final 6 months.

Who should apply for the SPC?

The Applicant for the SPC must own the basic patent, but need not hold the relevant marketing authorisation. Thus, it is possible to secure an SPC based on a marketing authorisation held by a third party11.

When should the SPC application be filed?

An application for an SPC must be filed with the national Patent Office of the country concerned within the later of:

- 6 months from the date on which the first authorisation to place the product on the market is granted in that country; or

- 6 months from the date of grant of the basic patent.

If the basic patent expires before marketing authorisation is achieved, it may not be possible to secure an SPC even if issue of the marketing authorisation is imminent. Under such circumstances, it may be worthwhile filing an application for an SPC before expiry of the patent and following up with the marketing authorisation when it is available. However, the case law of the CJEU has confirmed that Patent Offices should take a strict approach on this point and so the prospects for success are low 12.

What are the substantive requirements for obtaining SPCs?

The requirements for grant of an SPC are set out in Article 3 of the SPC Regulation.

- Article 3(a) requires that the product be “protected” by a basic patent.

- Articles 3(b) and 3(d) require that the SPC be based on the first valid authorisation to place the product on the market as a medicinal product.

- Article 3(c) requires that the product has not already been the subject of an SPC.

Although these requirements may appear relatively simple, each has been subject to multiple referrals to the CJEU. More detailed discussion is provided below.

What is meant by “protected” by a basic patent?

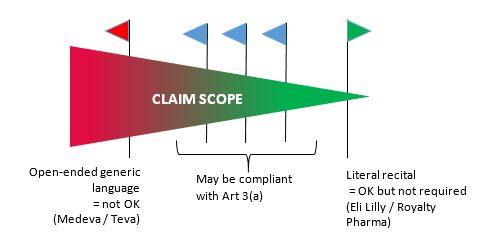

Perhaps surprisingly, to fulfil this requirement it is not sufficient that the product is embraced by the claims of the basic patent. The CJEU has explicitly indicated that compliance with Article 3(a) is not assessed by an infringement test. Rather, the active ingredient must be identified in a claim of the basic patent with at least some level of specificity. CJEU case law has evolved through a line of cases including the “Medeva”13 and “Eli Lilly”14decisions, and more recently the “Teva”15 and “Royalty Pharma”16 decisions, all of which have addressed the Article 3(a) requirement.

The consensus is that this line of cases has arrived at a strict interpretation of Article 3(a), requiring a patent claim which focusses on the active ingredient with a high level of specificity. Unfortunately, however, despite these many referrals to the CJEU it is still not completely clear what must be done to comply with Article 3(a), particularly in the absence of a patent claim focussed solely on the specific active ingredient (e.g. a claim to a single chemical compound, or to an antibody defined by its sequences). For combination products there is additional uncertainty as to whether even a narrow claim to the specific combination of active ingredients is sufficient under certain circumstances. This applies particularly when the patent (also) concerns a single active ingredient and/or its use as a monotherapy, which may have given rise to a monotherapy SPC based on the same patent. Some more detailed comments on the leading cases of the CJEU concerning Article 3(a) are provided below.

In Medeva, the CJEU held that for the SPC to be granted, the active ingredient must be “specified in the wording of the claims of the basic patent”.

The decision in Medeva was made in the context of SPCs for a combination therapy. Specifically, the patent had a claim to A, which would prevent an unauthorised third party from manufacturing and selling a medicinal product containing A and another active ingredient, B. However, this was held not to support an SPC for the product A+B because B was not specified in any way in the wording of the claim.

This has generally been interpreted to mean that a patent which claims product A and does not mention combination therapies cannot support an SPC for combinations of active ingredients containing A, e.g. an SPC for A+B17, even though the claims of the patent would embrace combinations of A with any other ingredient.

A subsequent CJEU decision18 confirmed that a patent which claims only a combination of A+B cannot be the basic patent for an SPC for A alone, despite the fact that sale of A may well, under some circumstances, infringe the patent under “contributory infringement” provisions. This remains true even where the marketing authorisation is for a medicine comprising A and includes an indication that A may or should be used together with B.

There has been much debate over the extent to which the reasoning in Medeva and other “combination” decisions should apply to single active ingredients. Clearly the requirement that the active ingredient is “specified” will be satisfied for a single active ingredient if the basic patent contains a claim which is specifically directed to that active ingredient. The situation is much less clear, though, when the claims of the basic patent embrace the product at without mentioning it explicitly.

In Eli Lilly, the CJEU explored this question in the specific context of a functionally defined active ingredient (“…an antibody which binds to <target>…”). It was held that a functional definition can in principle support an SPC, and an individualised disclosure is not necessary, provided that the claims when construed in the context of the description relate “implicitly but necessarily and specifically” to the active ingredient.

Although very little guidance was provided as to how to establish whether a claim meets this test, the referring UK Court19 interpreted the CJEU’s intention to be that any general claim language which covers a single active agent, including a functional definition, will satisfy the requirements of Article 3(a) for an SPC directed to that active agent. This remains the case even if there is no “individualised description” of the active ingredient elsewhere in the patent. However, claims which embrace active ingredients only by virtue of open-ended language, such as “comprises”, would not satisfy Article 3(a). Other national courts have come to a different view when faced with similar facts.

Perhaps reflecting a general frustration with the lack of clarity on this issue following Medeva and Eli Lilly, the referrals in Teva and Royalty Pharma followed20. Taken together, these two decisions suggest that Article 3(a) is satisfied provided that the following two conditions are met:

- The product must, from the point of view of a person skilled in the art and in the light of the description and drawings of the basic patent, necessarily fall under the invention covered by the basic patent.

- The person skilled in the art must be able to identify the product specifically in the light of all the information disclosed by that patent, on the basis of the prior art at the filing date or priority date of the patent concerned.

As with the earlier cases, neither Teva nor Royalty Pharma provided detailed guidance regarding how these criteria should be assessed. The latter did at least affirm that there is no requirement for the product to be explicitly disclosed as an individual embodiment. However it also went on to state that, when the product is not explicitly identified in the claims (instead e.g. falling within a general functional definition), the skilled person must be able to deduce directly and unambiguously from the specification of the patent as filed that the product falls under the invention covered by the basic patent. The CJEU also suggested that the provisions of Article 3(a) would not be satisfied if such a product was developed after the filing date, following an independent inventive step. This may imply that the mere existence of a later patent with more specific claims to a product (e.g. a selection invention patent) may be sufficient to exclude SPC protection based on an earlier broader patent, or at the very least that patent offices must conduct some form of assessment of inventive step when determining the validity of an SPC application under Article 3(a).

Even if the obvious problems with such an approach are ignored, there remains a lack of clarity as to the level of precision with which the skilled person must be able to identify a particular product. The strictest interpretation here could impose a requirement that the skilled person must have been able to identify the precise structural and/or functional characteristics of an individual product based on the teaching of the patent at the effective filing date.

Given the above, it is no surprise that the national courts of the EU/EEA have continued to struggle to apply a uniform approach to assessment of Article 3(a). This is reflected in two further referrals to the CJEU in late 2021/early 2022: one from the Finnish Market Court and one from the Supreme Court of Ireland21.

Both referrals relate to combination products and are not limited to Article 3(a). This is because in both cases the courts were concerned with an apparent tension between the reasoning applied by the CJEU when considering Article 3(a) in the line of cases culminating in Teva and Royalty Pharma, and the reasoning applied by the CJEU in earlier cases relating primarily to Article 3(c). The latter requires a focus on assessment of what is the “sole” or “core” invention protected by a basic patent, which the former has explicitly dismissed (see further discussion of Article 3(c) below under “How many SPCs may be granted for a given product or patent?”).

Regardless of the motivation for the referral, the questions of the Supreme Court of Ireland relating to Article 3(a) can be paraphrased as follows:

- Does it suffice that the product (i.e. the specific active ingredient or combination of active ingredients) is expressly identified in the patent claims OR is it necessary that product demonstrates novelty and inventive step or falls within a narrower concept described as the invention covered by the patent?

- If the latter, how is this to be assessed?

- If the patent is for a particular active ingredient, A, but the claims refer to its use both alone and in combination with other active ingredients, such as B, does Article 3(a) permit grant of an SPC only for A as a monotherapy, or can an SPC also be granted for any or all of the combination products, such as A+B?

It is hoped that the CJEU provide clear responses to each of these questions. In the meantime, we suggest that the interpretation of Article 3(a) is best viewed as a spectrum, as illustrated below:

Best practice: include at least a dependent claim focused as narrowly as possible on the active ingredient. For certain scenarios with combination products even a picture claim may not be sufficient, but the existence of such a claim in the granted patent will place the applicant in the best possible position.

What is meant by “a valid authorisation to place the product on the market as a medicinal product”?

The CJEU has confirmed that an SPC for a given product should be based on the first authorisation for a drug containing the product even if this is a combination therapy which includes the product. Thus, for example, an SPC for product A can be based on a patent claiming A and a marketing authorisation for a medicinal product containing A+B22. This may be important for vaccine products, where marketing authorisations often relate to combinations of multiple active ingredients. An SPC granted under such circumstances will cover all products containing product A approved before the SPC expires.

Which Marketing Authorisation is the first Marketing Authorisation?

Article 3(d) of the SPC Regulation requires that an SPC be based on the first authorisation to place a drug on the market as a medicinal product (the earliest marketing authorisation). The proper identification of the earliest marketing authorisation may be an issue when a patent protecting a second or subsequent medical use of a particular drug is used as the basis for an SPC application.

In the Yissum decision23, the CJEU confirmed that a patent to a new medical use of a drug could form the basis of an SPC, but held that the SPC must be based on the earliest marketing authorisation for that drug, even if the earliest authorisation was for a different disease or condition from that specified in the patent. In practice, reference to the earliest marketing authorisation often meant that any resultant SPC would have a zero term, because of the maximum SPC term of 15 years from first marketing authorisation in the EU.

Many were surprised when the landmark “Neurim” decision24 introduced a more generous interpretation taking into account the scope of the claims of the basic patent. Neurim established that the first marketing authorisation under Article 3(d) was the first such authorisation falling within the limits of the protection conferred by the basic patent. This opened the door to SPCs for new uses of known drugs based on downstream patents and later marketing authorisations, provided the patent claims excluded the product as specified by earlier marketing authorisations. There was much debate over how broadly the principles outlined in Neurim should be applied, with the various national patent offices diverging to a significant extent25.

Perhaps inevitably, this led to additional referrals in “Abraxis”26 and “Santen”27. Santen can now be considered the leading decision. Explicitly critical of the logic in Neurim, the Santen decision effectively returns the interpretation of Article 3(d) to that of Yissum. In short:

The first marketing authorisation is the earliest marketing authorisation for the active ingredient(s), irrespective of the disease indication or any other characteristics such as formulation, dose regime or patient group.

How many SPCs may be granted for a given product or patent?

Although Article 3(c) of the SPC Regulation suggests that only one SPC can be granted for a given product, it has long been the case that if two basic patents are owned by different Patentees, each Patentee can secure an SPC. Under such circumstances, both SPCs can be based on the same marketing authorisation.

If two patents which cover a given product are held by a single Patentee, only one SPC is available. The Patentee must choose which patent to use to support the SPC. Considerations which may apply when determining which patent to choose will include the relative vulnerability of the patents and the SPCs to any validity challenge and the duration of the SPC available from each patent.

In general, it is also possible to have multiple SPCs granted for multiple different products on the basis of the same basic patent, provided that each product is protected by the basic patent28.

An exception to this principle has however been set out by the CJEU in two cases29, both of which relate to a scenario in which an SPC has already been granted for a single active ingredient A, and a later application is filed for an SPC for a combination containing that active ingredient, A+B. The CJEU has held that the later SPC should not be granted in these circumstances.

However, the reasoning of the CJEU in both cases appears to have been influenced by a finding that the single active ingredient was the “sole” or “core” of the invention underlying the basic patent, and so they were reluctant to award a further SPC for the combination. It is unclear whether the exception would also apply if the combination represented a separate inventive advance disclosed within the same patent, or indeed if the combination had been presented in a separate patent.

This lack of clarity has clearly contributed to the two further referrals to the CJEU in late 2021/early 2022 that are discussed above in connection with Article 3(a): one from the Finnish Market Court and one from the Supreme Court of Ireland21 . Both cases are concerned with combination therapies where an SPC has already been granted for one of the active ingredients, and the courts are seeking guidance as to whether an assessment of the “core” invention can or should be used to preclude grant of a further SPC to a combination based on the same patent.

The questions of the Supreme Court of Ireland relating to Article 3(c) can be paraphrased as follows:

- Is the grant of an SPC limited to the first marketing of an active ingredient A whether as a monotherapy product or as a combination product A+B, such that (following that first grant) there cannot be grant of a second or third SPC for any other monotherapy or combination therapy which is claimed in the patent?

- If the claims of a patent cover both a single novel molecule and a combination of that molecule with another (known) drug, or several such claims for a combination, does Article 3(c) limit the grant of an SPC:

(a) only to the single molecule if marketed as a product;

(b) only to the first marketed product covered by the patent, whether it be the monotherapy or the first combination therapy; or

(c) either (a) or (b) at the election of the patentee irrespective of the date of market authorisation?

- If any of (a), (b) or (c) apply, why?

As with Article 3(a), it is hoped that the CJEU provide clear responses to each of these questions. Ideally they will also take the opportunity to explain whether the same reasoning applies when a (combination) product represents a separate inventive advance disclosed in the same patent, a related patent (such as a divisional), or an entirely separate patent.

Is it possible for a third party to challenge the grant of the SPC?

Even where there is no formal mechanism to do so, most national patent offices will consider observations filed by a third party against an application for an SPC. Such observations may draw the Examiner’s attention to deficiencies in the application with respect to compliance with the substantive requirements of the SPC Regulation. Such observations may slow (or even prevent) grant of the SPC application. After grant, the validity of an SPC may be challenged in the national courts on the same grounds.

The validity of the basic patent underlying an SPC may of course also be challenged separately via all normal routes (EPO opposition, national revocation action etc.). Should the patent be revoked, any SPC or SPC application based upon it is automatically invalidated.

Annex

Regulation (EC) No 469/2009 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 6 May 2009 (selected provisions)

Article 1

Definitions

For the purposes of this Regulation, the following definitions shall apply:

- ‘medicinal product’ means any substance or combination of substances presented for treating or preventing disease in human beings or animals and any substance or combination of substances which may be administered to human beings or animals with a view to making a medical diagnosis or to restoring, correcting or modifying physiological functions in humans or in animals;

- ‘product’ means the active ingredient or combination of active ingredients of a medicinal product; […]

Article 2

Scope

Any product protected by a patent in the territory of a Member State and subject, prior to being placed on the market as a medicinal product, to an administrative authorisation procedure as laid down in Directive 2001/83/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 6 November 2001 on the Community code relating to medicinal products for human use or Directive 2001/82/EC of the European

Parliament and of the Council of 6 November 2001 on the Community code relating to veterinary medicinal products may, under the terms and conditions provided for in this Regulation, be the subject of a certificate.

Article 3

Conditions for Obtaining a Certificate

A certificate shall be granted if, in the Member State in which the application referred to in Article 7 is submitted and at the date of that application:

- the product is protected by a basic patent in force;

- a valid authorisation to place the product on the market as a medicinal product has been granted in accordance with Directive 2001/83/EC or Directive 2001/82/EC, as appropriate;

- the product has not already been the subject of a certificate;

- the authorisation referred to in point (b) is the first authorization to place the product on the market as a medicinal product.

Article 4

Subject matter of protection

Within the limits of the protection conferred by the basic patent, the protection conferred by a certificate shall extend only to the product covered by the authorisation to place the corresponding medicinal product on the market and for any use of the product as a medicinal product that has been authorised before the expiry of the certificate.

Article 5

Effects of the certificate

Subject to the provisions of Article 4, the certificate shall confer the same rights as conferred by the basic patent and shall be subject to the same limitations and the same obligations.

Footnotes

- SPCs are also available for active substances in plant protection products, but these are not the focus of this briefing.

- The purpose is thus similar to Patent Term Extensions (PTE) available in e.g. USA and Japan, but unlike those systems an SPC is not an extension of a patent, it is a separate right.

- C-431/04 MIT (a bioerodible matrix) & C-210/13 Glaxosmithkline (an adjuvant in a vaccine)

- The UK officially left the EU at 11pm UK time on 31 January 2020, at which point it entered an implementation (or transition) period. During the implementation period, EU law relevant to SPCs continued to apply directly in the UK. The implementation period ended at 11pm UK time on 31 December 2020, at which point the corresponding provisions transposed into UK national law came into effect.

- Swiss marketing authorisations also automatically take effect in Liechtenstein, which unlike Switzerland is an EEA member. Thus this must be taken into account when determining the first authorisation in the EU/EEA. See comments on additional term provided by an SPC below.

- C-322/10 Medeva, C-422/10 Georgetown and C442/11 Novartis v. Actavis

- C-392/97 Farmitalia

- Pharmaq v Intervet 15-170539ASD-BORG/01

- Similar status to the CJEU for matters referred by the national courts of the EEA states: Norway, Iceland, Liechtenstein.

- The CJEU confirmed in C-471/14 that the relevant date of an EU Marketing Authorisation is the date on which notification of the authorisation is made to the holder (typically a few days later than the Commission Decision granting the authorisation). This may result in extra days of SPC term, although some national patent offices have yet to correct the term of SPCs granted prior to the CJEU decision. A further referral (C-492/169) from the Hungarian Courts asks whether such correction is required. A hearing date has not yet been set.

- C-181/95 Biogen V SKB explicitly endorsed this view.

- In C-567/16 the CJEU confirmed a strict interpretation of the requirement for an issued marketing authorisation. An “end of procedure” notice (indicating that an MA is imminent) was held not sufficient to support an SPC. The CJEU also held that the absence of a full MA was not a formal irregularity that could be remedied later.

- C-322/10

- C-493/12

- C-121/17

- C-650/17

- [2012] EWCA Civ 523 Medeva BV v Comptroller General of Patents

- C-518/10 Yeda

- [2014] EWHC 2404 (Pat) Eli Lilly

- In fact there was also a 3rd additional referral under Article 3(a) (C-114/18 Sandoz v Hexal), but this was withdrawn before judgement. It asked whether Article 3(a) is satisfied where a product is explicitly encompassed by a Markush formula in the claims, but the particular active ingredient is not mentioned anywhere in the patent (and possesses an unusual substituent).

- MSD v Teva and MSD v Clonmel

- C-322/10 Medeva and C-422/10 Georgetown

- C-202/05 Yissum

- C-130/11 Neurim

- A patent claim can of course be limited to exclude a marketing authorisation on the basis of characteristics other than disease indication. Some national offices applied Neurim very narrowly, such that an SPC was only granted if the excluded earlier authorisation was veterinary and the later authorisation was for a different indication in humans (the precise scenario in Neurim). Many offices applied a broader interpretation, such that the SPC was granted provided the later authorisation was for any different indication to the excluded earlier authorisation. Other offices applied Neurim very broadly, such that an SPC was granted if the later authorisation differed from the excluded earlier authorisation in any way, including e.g. formulation, dose regime or patient group.

- C-443/17 Abraxis

- C-673/18 Santen

- C-484/12 Georgetown

- C-443/12 Actavis v Sanofi, C-577/13 Actavis v Boehringer