The Unified Patent Court (UPC)

The European Patent Convention (EPC), as applied by the European Patent Office (EPO), is one of the main sources of law of the Unified Patent Court Agreement. The procedure of the Unified Patent Court also, to a large extent, mirrors the Opposition procedure at the EPO. European Patent Attorney UPC Representatives thus have unique skills required for successful representation at the UPC. With one of the most highly and universally respected opposition practices in Europe, J A Kemp is well placed to help clients navigate the early days of the UPC as the new court develops its procedures and case law.

Why litigate at the Unified Patent Court?

The primary advantage of the Unified Patent Court, for patentees, is that it operates as a single court with jurisdiction over multiple European countries. Currently 18 countries have ratified the Unified Patent Court Agreement and eventually it is hoped that 25 countries in total will ratify the agreement. An infringement action brought at the UPC could, under these circumstances, cover all EU countries except Spain and Croatia.

The wide jurisdiction of the UPC means that a European Patent can be enforced in multiple countries via a single infringement action brought at the UPC. This is considerably less expensive than bringing separate infringement actions before the national courts of each country where there is infringing activity. It also avoids the undesirable outcome of national courts in different European countries coming to different conclusions.

As regards the UPC court procedure, the UPC is designed specifically for patent litigation. The procedural rules of the UPC enable a number of advantages for a patentee seeking to enforce a patent.

- Patents granted in English are likely to be litigated in English. This reduces translation costs, and enables English-speaking litigants to understand and participate fully in the litigation.

- The UPC has the power to order an alleged infringer to disclose to the patentee relevant material under their control, e.g. by providing details of the product or process said to infringe the patent. The UPC can also enable a patentee to secure evidence of infringement via a saise-contrefaçon procedure, whereby court officials can gain access without notice to the business premises of an alleged infringer.

- The Rules of Procedure for the UPC envisage that the first instance decision should be achieved within a timescale of 12 to 15 months, with a similar amount of time for the appeal. Initial first instance decisions have been issued in the promised timeframe, which compares favourably to current national court timescales. The court should therefore provide an effective remedy within a realistic timeframe.

- The UPC has the power to award costs against a losing party.

Thus, if a patentee successfully establishes infringement of a valid patent before the UPC, they can recover a proportion of their legal costs from the losing party.

Decisions from the UPC are likely to be of high quality. This is because, first instance UPC cases will be heard by a panel of three experienced and specialist intellectual property judges. The plan is that at least one of the first instance UPC judges will be an IP specialist judge from the existing national courts. This ought to ensure high quality decisions from the outset. There will be a Court of Appeal which will sit as a panel of five experienced appeal judges.

Jurisdiction and structure of the Unified Patent Court

Unitary Patents can only be litigated in the Unified Patent Court. A single action will be used to enforce the patent against an alleged infringer in all of the UPC participating countries. This may lead to a single injunction across all the UPC participating countries. Equally, a single action can be used to revoke a Unitary Patent in all UPC participating countries.

Where Unitary Patent protection is selected there is no option to opt out of the Unified Patent Court. By selecting a Unitary Patent, the proprietor is in effect positively choosing to use the Unified Patent Court.

The Unified Patent Court also has jurisdiction over European patents validated in UPC participating countries unless the European Patent has been proactively opted out. Opting out is only available for national validations of a European Patent, and is not an option for a Unitary Patent. The ability to opt out European Patents validated in UPC participating countries will cease after a transitional period, initially set at 7 years.

National courts have exclusive jurisdiction over national validations of European patents which have been opted out of the UPC and for national validations in countries not participating in the UPC.

The Unified Patent Court comprises a Court of First Instance and a Court of Appeal. The Court of First Instance comprises a central division and a number of local and regional divisions. Local divisions have responsibility for actions brought in respect of infringement in individual participating countries. Regional divisions have similar responsibility, but for a number of participating countries. Local divisions have been confirmed in Germany, Italy, France, the Netherlands, Belgium, Finland, Denmark, Austria, Portugal and Slovenia. A Nordic-Baltic regional division based in Stockholm has also been confirmed, covering Sweden, Lithuania, Estonia and Latvia.

The central division is currently split between France, Germany and Italy. The headquarters of the central division will be in Paris.

The Paris section of the central division deals particularly with patents in fields including electronics, software and physics The Munich section of the central division deals particularly with patents relating to mechanical engineering. The Milan section of the central division deals particularly with patents in the fields of chemistry, pharmaceuticals, biotechnology and also human necessities, including medical devices. If a patent has classification codes in different fields of technology, it will be allocated to the section of the central division responsible for the first-mentioned classification code.

Representation at the UPC

Any lawyer authorised to practice before a court of a participating country and any suitably qualified European Patent Attorney (including attorneys from all offices of J A Kemp) may represent a party before any division and the Court of Appeal of the UPC.

Responsibility of local and central divisions

The local (and regional) divisions and the central division have separate responsibilities. Any action for infringement is generally brought before a local or regional division. If the defendant counter-claims for invalidity, the local or regional division may also hear the invalidity action.

By way of exception from this general rule, infringement actions can be brought before the central division if (a) the parties agree or (b) the defendant does not have a place of business in any UPC participating country.

To challenge the validity of a patent at the UPC, other than as a counterclaim in an infringement action, it is necessary to bring an action at the central division. An action seeking a declaration of non-infringement must also be brought at the central division.

Where actions can be brought

Claimants must bring infringement actions in the local/regional division where the actual or threatened infringement has occurred or may occur, or the local/regional division where the defendant has its residence or principal place of business. If the defendant has no residence or place of business in a participating country, then the claimant may bring an action either where the infringement occurred or, if the participating country has no local or regional division, before the central division.

If a defendant in an infringement action files a counterclaim for revocation, the counterclaim must be brought in the local/regional division hearing the infringement action. The local/regional division may then either (a) proceed with a single action which considers both infringement and validity, (b) refer the counterclaim for revocation to the central division and either suspend or proceed with the action for infringement or (c) refer the entire case to the central division.

If an action for revocation is pending before the central division, then an action for infringement between the same parties relating to the same patent may be brought in the local/regional division, where the defendant has its place of business or where an infringement has taken place. Alternatively, under these circumstances, the infringement action can be brought in the central division.

If an action for a declaration of non-infringement is brought before the central division, the central division will stay the action if an infringement action between the same parties (or between an exclusive licensee of the patentee and the same defendant) relating to the same patent is brought before a local or regional division within 3 months of the date on which the action was initiated before the central division.

Notwithstanding all of the above, parties may agree to bring any action before the division of their choice, including the central division.

Language

Local or regional divisions hear cases either in one of the official languages of the host country or any other language designated by the division. All divisions have designated English. Further, the parties may agree, subject to approval by the court (or the court may decide, subject to the agreement of the parties), to hear the case in the language in which the patent was granted. One party may request that the case be heard in the language of the patent. In such a case the position of the defendant in particular must be taken into account.

The central division hears cases in the language the patent concerned was granted.

The Court of Appeal, except in exceptional circumstances, uses the same language as used in the Court of First Instance, or the parties may agree to use the language in which the patent was granted.

Around 75% of European Patents are granted in English and the majority of cases before the local, regional and central divisions of the UPC in its first year of operation have been heard in English.

Applicable law

Articles 138 and 139 of the EPC represent the applicable law for validity.

The law for infringement is the national law of a participating country which is determined based on the nationality or place of business of the first named applicant at the time of filing of the patent.

In practice, determining the law for infringement may not be of much significance. That is because the law in all EU countries ought to comply with Chapter II of the Community Patent Convention (CPC). The definition of infringement given in articles 25-28 of the Agreement for a Unified Patent Court (UPCA) corresponds almost word for word with that in the CPC. Further, the UPC is not bound by any national law precedent, so it will likely create its own case law and interpretation of what is the ‘original’ black letter law of infringement across Europe: the CPC, as repeated by the UPC Agreement.

The default law governing the patent as an object of property (i.e. the law governing assignment, licensing, mortgaging etc. of the patent) will be the same law as applies for infringement. However, the Rome I Regulation will apply here, which means that parties to a licence or co-ownership agreement are free to choose themselves which law should apply to the agreement.

Appeals

Appeals to the Court of Appeal in Luxembourg are available as of right on (a) final decisions, (b) decisions which terminate proceedings as regards one of the parties and (c) decisions on certain types of orders including those relating to language, production of documents, preservation of evidence/inspection of premises, freezing orders, protective measures, and orders to communicate information.

Other types of orders may only be appealed together with the appeal against the final decision, or if the court grants leave to appeal on request by the appellant.

Appeals are to be based both on points of law and on matters of fact, but new facts and new evidence may only be introduced when the party introducing the new material could not reasonably have been expected to submit them during proceedings before the Court of First Instance.

Appeals against final decisions will cause that decision to be suspended, while appeals against interim orders made in pending cases will not stay the main proceedings, albeit that the Court of First Instance will not give a decision in the main proceedings before a decision of the Court of Appeal on any in-suit applications.

The Court of Appeal may either overturn the decision of the Court of First Instance and give a final decision, or refer the case back to the Court of First Instance.

Unified Patent Court procedure, remedies, and fees

In summary, the procedure comprises a Written Procedure, in which the parties submit statements of case, an Interim Procedure in which preparations for trial are made, and an Oral Procedure. The rules include hard deadlines for the steps of the Written Procedure including just 3 months for filing a defence to an infringement action and a counterclaim for revocation, and 2 months for filing a reply to the defence and a defence to the counterclaim for revocation. The rules envisage that the first instance procedure should be completed in 12 to 15 months, with a similar period allowed for the appeal.

Final orders obtainable

The UPC is able to order the revocation of a patent, either entirely or partly.

In infringement proceedings the court may order an injunction against the infringer aimed at prohibiting the continuation of the infringement. The court may also grant an injunction against an intermediary providing services being used by a third party to infringe a patent. In addition, the court may order that infringing products, at the expense of the infringer, be:

- recalled from channels of commerce;

- deprived of their infringing property; or

- destroyed, together with materials and implements used to produce the products.

Further, the UPC is able to order an infringer to pay damages to compensate the patentee (or exclusive licensee) for losses suffered as a result of the infringement. Damages will be compensatory, not punitive. The patentee’s lost profit, unfair profits made by the infringer and non-economic factors such as moral prejudice can be taken into account when assessing the level of damages payable. An infringer can avoid paying damages if he can demonstrate that he did not know, and had no reasonable grounds to know, that he was infringing the patent, although payment of compensation or the recovery of profits may still be ordered.

Interim orders obtainable

A variety of interim orders are available.

Interim injunction: The court may order an alleged infringer to cease, or not to commence, activities said to infringe a patent while the issue of liability is considered.

Disclosure of evidence: If a party presents reasonable evidence sufficient to support its claims that necessary documents or information (relating either to liability or to quantum of damages or to the validity of the patent) is in the control of the opposing party or a third party then the court may order that other party to disclose the relevant material, with measures being available to protect confidential information.

Evidence preservation: The court may, before commencement of proceedings on the merits of the case, order ex parte measures (inspecting premises, taking samples, seizing products, materials and implements used in the production and/or distribution of those products and documents relating thereto) to preserve relevant evidence in respect of the alleged infringement. These orders may be subject to a bond, and an applicant seeking such an order may have to compensate a defendant for damage suffered as a result of an evidence preservation order if it is subsequently found that there was no infringement or if the applicant fails to pursue the case.

Other types of order

The court may order a party not to remove from its jurisdiction any assets located therein, or not to deal in any assets, whether located in its jurisdiction or not. It is likely that these interim orders will require a further order by the national court of the relevant country to enforce.

The court may order an infringer, or in certain circumstances a third party, to disclose:

- the origin and distribution channels of the infringing products or processes;

- the quantities produced, manufactured, delivered, received or ordered as well as the price obtained for the infringing products; and

- the identity of any third person involved in the production or distribution of the infringing products or the use of any infringing process.

Evidence and the burden of proof

As usual in civil litigation, any party seeking to rely on a fact has the burden of proving it and may rely on witnesses, experts, inspection, experiments or comparative tests, affidavits, documents, requests for information, and party submissions. The UPC agreement gives no indication as to the relative weight of each of those types of evidence.

The burden of proof can be reversed if the subject matter of the patent is a process for obtaining a new product, and the infringing product is identical to the product produced by the patented process.

Court experts

The court may appoint court experts to provide expertise for specific aspects of the case. A list of approved experts is kept by the Registrar to guarantee independence and impartiality.

Fees

The UPC is intended to be self-financing and court fees are payable. The value-based court fees can be found here and further information on calculating the value of a case can be found here.

Costs

The UPC agreement states that reasonable and proportionate legal costs and other expenses incurred by the successful party shall as a general rule be borne by the unsuccessful party. Further information relating to the levels of recoverable costs can be found here.

Enforcement of orders

Enforcement proceedings shall be governed by the law of the participating country where the enforcement takes place.

The UPC can sanction non-compliant parties with a recurring penalty proportionate to the importance of the order to be enforced.

Arbitration and mediation

A patent mediation and arbitration centre is seated in Ljubljana and Lisbon, and a list of mediators and arbitrators is held by the UPC.

Parties entitled to bring an infringement action

The patent proprietor is entitled to bring infringement actions. An exclusive licensee may bring an infringement action as long as the licence agreement does not prohibit it, and it gives prior notice to the proprietor. A non-exclusive licensee may bring an infringement action if the licence agreement expressly permits it, and it gives the proprietor prior notice.

Opting out of the UPC

It is possible for patentees to avoid the threat of an action at the UPC by filing a request to opt out nationally validated European patents of the jurisdiction of the UPC. An opt out needs to be filed for each European patent which is to be opted out. If such an opt out is not registered before the opening of the UPC, third parties may start an action at the UPC when it opens. After a UPC action has commenced, it is no longer possible to opt out.

A patent that is opted out is not enforceable via the UPC. However, it is possible to withdraw the opt out, for example in preparation for any litigation that the patentee themselves would like to initiate at the UPC, so long as no national litigation has commenced.

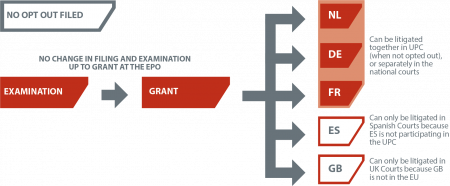

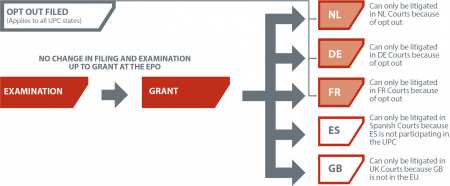

As shown in the example below, if no “opt out” is filed, the UPC shares jurisdiction with the national courts in the countries in which the UPCA takes effect. However, this does not apply to all EPC countries. For example Spain (ES) is not participating in the UPC and the United Kingdom (GB), for example, is one of a number of EPC countries which are not member countries of the EU. As a result, jurisdiction for Spain and the United Kingdom and other non-participating countries remains solely with their national courts (no shading).

If an opt out is filed, jurisdiction for all of the validated countries remains solely with the national courts (see next diagram).

Matters for consideration in deciding to opt out

If you need advice regarding whether or not to opt out a European patent, please do not hesitate to contact us. Some of the main considerations in deciding whether to opt out are set out below.

Reasons patentees may wish to avoid the jurisdiction of the UPC by opting out include:

- the threat of a single central revocation action (currently actions need to be brought in national courts of each country in which the European patent is in force)

- concern about exposing patents to the jurisdiction of a completely new, unfamiliar and untested court

- concern about the cost of defending an action at the UPC and the threat of an adverse costs finding resulting from an unsuccessful defence of a revocation action

- concern about the short deadlines for responding to a revocation action in the UPC

Reasons patentees may not wish to opt out of the jurisdiction of the UPC include:

- a desire to be involved in development of the UPC from the outset

- to avoid the administrative burden and cost of the opt out process

- to ensure that central enforcement in the UPC is available and that a third party cannot commence a national action to prevent withdrawal of an opt out

Practicalities of requesting an opt out

Any opt out request is made in respect of all the “states for which the European patent has been granted” and the opt out application must list the name(s) and address(es) of the patent proprietor(s) (patentee/patent owner). We understand this to mean that, for each country listed on the published European patent (B specification), the true patentee/patent owner must be listed in the opt out request and give their consent to the filing of the opt out. The request must be accompanied by a declaration that the named proprietor is entitled to be registered in the national patent register (not necessarily actually registered).

If any SPCs exist based on a patent, the SPC(s) and the SPC owner(s) also need to be named (and the owner(s) needs to give permission to file the opt out).

A third party can challenge an opt out on the basis that the wrong states and/or proprietor has been named, or that consent to file the opt out was not given: it is therefore important to check that details on the identity of the patent proprietor are upto-date; the national register may not be correct as transactions may not have been recorded.

If an opt out is filed in a case where at least one national register is out of date, we recommend updating the national register(s) accordingly. First, this will prevent a prima facie challenge to the opt out. Second, in many European countries damages can be withheld for periods where a national register is not up-to-date regarding the proprietor information.

The rules relating to filing an opt out are not comprehensive nor wholly clear. Only case law will clarify what is required for a valid opt out. We think the following will reduce the chance of an opt out being successfully challenged:

- clear consent from a duly authorised officer of each proprietor to file the opt out

- original assignment documents (if any) showing transfer of application/patent from the originally named filing applicant(s) to the proprietor(s) named on the opt out request, for each country listed on the B specification of the patent

- up-to-date national registers which show the same proprietors as named in the opt out request.

For cases that have never been assigned from the original applicant(s), or where an assignment occurred only pre-grant and was recorded at the EPO, these requirements may not be very onerous. For cases assigned after grant, it will be necessary to consider the assignment document to establish whose consent is needed for the opt out and who should be named in the opt out request in respect of each of the countries listed on the B publication of the patent, whether or not validated there or whether or not still in force.