World Vegetarian Day: “Meat” the future of food

The number of people following a vegetarian or vegan diet is increasing. Whilst exact numbers are hard to establish, data based on surveys published by the UK Vegan society suggest that the number of vegans has quadrupled in recent years.

The reasons behind this are likely to be manifold but growing awareness of the CO2 emissions caused by the meat industry as well as concerns for animal welfare are most probably major contributing factors. At least some of the people who make the switch due to environmental reasons likely enjoy the taste of meat and will be looking for alternatives. There is an even greater number who wish to reduce their meat intake without turning fully vegetarian or vegan and without having to miss out on the foods they like. This demand has sparked a growing industry which provides meat substitutes.

The global meat substitute market is projected to grow to a staggering USD 12.3 billion by 2029 according to Fortune Business Insights. Recent years have also seen a surge in the number of inventions aimed at making meat substitutes taste like the real thing.

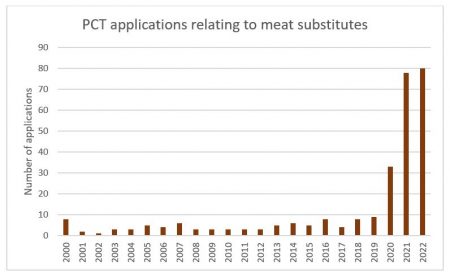

The increase in innovation is accompanied by an increase in patent applications relating to meat substitutes. This is reflected in the number of PCT patent filings which have increased at least ten-fold in the last years.

There are different approaches to providing meat substitutes but broadly companies either produce meat analogues or cultured meat.

Meat analogues

Meat analogues are those where the product itself does not contain any animal cells but the texture and taste of meat are mimicked by plant or microbial materials.

Perhaps one of the most widely known meat analogues is a microbial biomass produced from the Fusarium venenatum fungus, which is marketed as Quorn™. To obtain the product the fungus is fermented in large bioreactors, harvested and pressed into its final shape. Numerous applications have been filed to protect this technology with the earliest European patent (EP0123434) dating back to 1983 and containing process claims directed to the core technology for obtaining the product.

Another product which has received a lot of attention in the press is a plant-based burger patty which contains an alternative to the iron-rich animal molecule heme which is credited with giving beef its distinct taste. This heme analogue was originally isolated from soy and has been named leghemoglobin. It is said to impart a beef-like flavour to soy-based beef patties.

Leghemoglobin has been a focus of patent protection. It is naturally occurring in the root nodules of soy and so a claim to the product itself would likely be considered to lack novelty. Accordingly, the patent strategy has revolved around claims directed to “beef-like” food products that contain the molecule. For example, one of the earliest US patents US9,700,067 claims a food product comprising inter alia an isolated heme-containing protein in combination with selected flavour precursors. Subsequent filings are directed to other aspects such as methods of imparting flavour or of recombinantly producing the plant heme. There are also applications claiming the production of the leghemoglobin which is produced recombinantly in genetically modified yeast. The presence of the isolated soy leghemoglobin certainly seems to have made the grant of product claims much more feasible.

A competitor who also provides beef alternatives is opting for a different strategy by not using genetically modified components. Instead, the beef-like taste is achieved by a particular combination of ingredients, including pea protein, coconut oil, mung bean protein, vinegar, lemon juice and others. The beef flavour and colour stems from beet juice and apple extract. The technical effect of having a beef-like flavour is thus not achieved by a novel defined molecule. Instead, it is the particular recipe for producing the burgers that gives the illusion of meat. This makes patent protection a bit more difficult, at least insofar as product claims are concerned. Perhaps not surprisingly, the patent portfolio therefore does not claim combinations of ingredients but rather approaches it from a different angle by claiming meat-like food products with a particular protein structure. For example, EP3361881 was filed with claims specifying inter alia a meat-like food product which contains “meat-structured” proteins.

Cultured meat

Other players in the market are choosing a different approach. Instead of finding plant based meat alternatives, they aim to develop lab-grown meats. To this end, animal cells are grown in culture to produce cultured meat and, in some cases, animal fat. Advocates for lab-grown meat point out that it significantly reduces the number of animals which need to be slaughtered. Another argument is that it is safer as it is grown in a fully controlled environment thus reducing the likelihood of contamination and avoiding the need for antibiotics and other additives.

The first burger produced from lab-grown meat was presented by Mark Post, a researcher at Maastricht University, in 2013 as a proof of concept. Reportedly, this burger cost more than USD 300,000 to develop and was found by testers to be “close to meat, but […] not that juicy”. Despite this early success, only one lab-grown meat product is currently available commercially (lab-grown chicken nuggets, which have been approved for sale in Singapore) and it is likely to take some more time before lab-grown meat products become mainstream. The reasons behind this are in part technical but there is also a consumer perception which views these “artificial meats” sceptically.

Unlike meat analogues, cultured meat is not made from plants but is derived from cultured animal cells. For example, the cultured chicken nuggets sold in Singapore are based on a chicken fibroblast cell line which is grown in vitro, mixed with other components, and subsequently shaped into “chicken nuggets”.

Of course, cell culture has been around for many decades and so is not new. This presents a unique challenge to those companies which are trying to patent their technology.

One of the most important aspects of any technology for growing cultured meat is the cell line. The cells must be able to replicate to reach a desired density and subsequently have the ability to differentiate into the mature cells that meat is made of. They must, however, also meet strict safety requirements and must not form tumours or be infected with any viruses or other pathogens. Usually, stem cells isolated from an animal are used.

As the cells are originally isolated from an animal it is likely difficult to obtain patent protection for the cell line per se as it will have been present in the animal and will thus, in many cases, not be distinguishable from the naturally occurring cells. Accordingly, not many patent applications can be found which aim to claim the original cell line per se. Another potential problem with claims directed to the cell line per se is that sufficiency of disclosure may be achieved only if the cells are deposited with a recognised depository institution. This bears the risk that the cells may become available to third parties. Such a step therefore needs to be carefully considered.

Due to these potential problems with claims directed to the cells per se, patent applications in the field are focussing on other aspects like the growth process, ways of differentiating the cells into the final muscle tissue and the growth on scaffolds to obtain a product that optically resembles meat. At least some of these applications have been granted with reasonably broad claims. For example, a patent was granted in Europe and the USA with claims directed to a meat product produced by a process in which certain animal cells are grown in the absence of hazardous substances into a three dimensional animal muscle tissue. Other granted cases cover improved growth conditions as well as processes for growing the cells on scaffolds.

Summary

Many obstacles remain before all meat products can be mimicked by a suitable meat substitute which resembles the original in taste, texture and nutrition. Thus, significant innovation can be expected in the field going forward. Patent protection for these innovations is useful and achievable but may sometimes require a creative claim strategy of its own. As the meat substitute industry continues to move into the mainstream and significant investments continue to be made, vegan meat is no longer science fiction but reality.