Opting out of the UPC

Opting out

It is possible for patentees to avoid the threat of an action at the UPC by filing a request to opt out nationally validated European patents of the jurisdiction of the UPC. An opt out needs to be filed for each European patent which is to be opted out. If such an opt out is not registered before the opening of the UPC, third parties may start an action at the UPC when it opens. After a UPC action has commenced, it is no longer possible to opt out.

A patent that is opted out is not enforceable via the UPC. However, it is possible to withdraw the opt out, for example in preparation for any litigation that the patentee themselves would like to initiate at the UPC, so long as no national litigation has commenced.

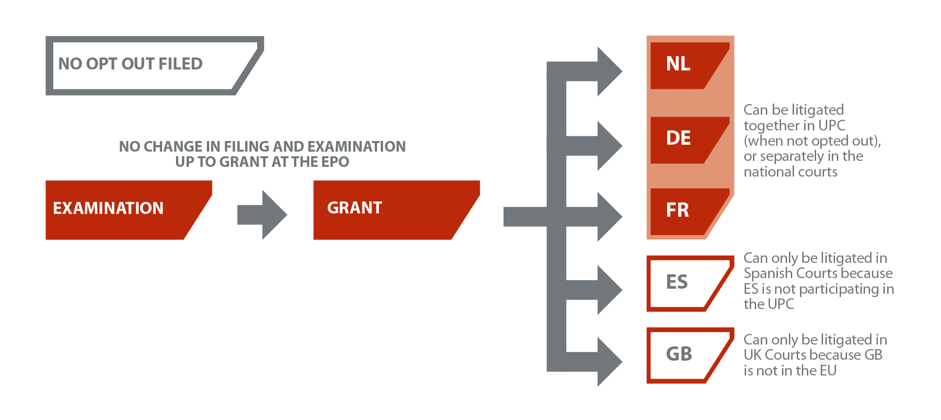

As shown in the example below, if no “opt out” is filed, the UPC shares jurisdiction with the national courts in the countries in which the UPCA takes effect. However, this does not apply to all EPC countries. For example Spain (ES) is not participating in the UPC and the United Kingdom (GB), for example, is one of a number of EPC countries which are not member countries of the EU. As a result, jurisdiction for Spain and the United Kingdom and other non-participating countries remains solely with their national courts (no shading).

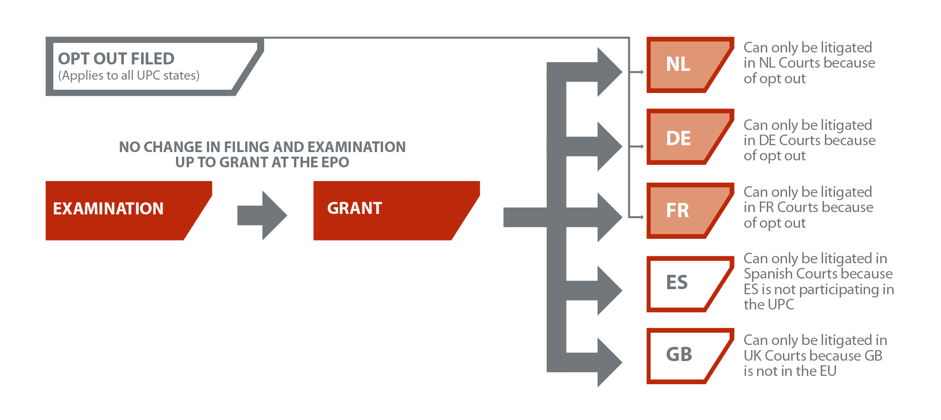

If an opt out is filed, jurisdiction for all of the validated countries remains solely with the national courts (see below).

Matters for consideration in deciding to opt out

If you need advice regarding whether or not to opt out a European patent, please do not hesitate to contact us. Some of the main considerations in deciding whether to opt out are set out below.

Reasons patentees may wish to avoid the jurisdiction of the UPC by opting out include:

- the threat of a single central revocation action (currently actions need to be brought in national courts of each country in which the European patent is in force)

- concern about exposing patents to the jurisdiction of a completely new, unfamiliar and untested court

- concern about the cost of defending an action at the UPC and the threat of an adverse costs finding resulting from an unsuccessful defence of a revocation action

- concern about the short deadlines for responding to a revocation action in the UPC

Reasons patentees may not wish to opt out of the jurisdiction of the UPC include:

- a desire to be involved in development of the UPC from the outset

- to avoid the administrative burden and cost of the opt out process

- to ensure that central enforcement in the UPC is available and that a third party cannot commence a national action to prevent withdrawal of an opt out

Practicalities of requesting an opt out

Any opt out request is made in respect of all the “states for which the European patent has been granted” and the opt out application must list the name(s) and address(es) of the patent proprietor(s) (patentee/patent owner). We understand this to mean that, for each country listed on the published European patent (B specification), the true patentee/patent owner must be listed in the opt out request and give their consent to the filing of the opt out. The request must be accompanied by a declaration that the named proprietor is entitled to be registered in the national patent register (not necessarily actually registered).

If any SPCs exist based on a patent, the SPC(s) and the SPC owner(s) also need to be named (and the owner(s) needs to give permission to file the opt out).

A third party could challenge an opt out on the basis that the wrong states and/or proprietor has been named, or that consent to file the opt out was not given: it is therefore important to check that details on the identity of the patent proprietor are up-to-date; the national register may not be correct as transactions may not have been recorded.

If an opt out is filed in a case where at least one national register is out of date, we recommend updating the national register(s) accordingly. First, this will prevent a prima facie challenge to the opt out. Second, in many European countries damages can be withheld for periods where a national register is not up-to-date regarding the proprietor information.

The rules relating to filing an opt out are not comprehensive nor wholly clear. Only case law will clarify what is required for a valid opt out. We think the following will reduce the chance of an opt out being successfully challenged:

- clear consent from a duly authorised officer of each proprietor to file the opt out

- original assignment documents (if any) showing transfer of application/patent from the originally named filing applicant(s) to the proprietor(s) named on the opt out request, for each country listed on the B specification of the patent

- up-to-date national registers which show the same proprietors as named in the opt out request.

For cases that have never been assigned from the original applicant(s), or where an assignment occurred only pre-grant and was recorded at the EPO, these requirements may not be very onerous. For cases assigned after grant, it will be necessary to consider the assignment document to establish whose consent is needed for the opt out and who should be named in the opt out request in respect of each of the countries listed on the B publication of the patent, whether or not validated there or whether or not still in force.