Inventive Step for Software Inventions at the EPO

The EPO has long adopted an approach to consideration of inventive step known as the problem and solution approach. Although this approach is fundamentally the same across most technical areas, special considerations apply for software related inventions. Firstly, the EPO looks for an invention to be the technical solution to a technical problem and so disregards non-technical aims/features, which are common in software fields. Secondly, the EPO Boards of Appeal often have quite high expectations of the capabilities of the ordinary person skilled in the art and thus a high threshold for inventive step. We discuss these issues below with particular reference to some cases that aim to provide a framework for consistent determination of what aims or features should be regarded as technical and what should not.

The problem and solution approach

The problem and solution approach as applied by the EPO to consideration of inventive step is normally a four step process. The first step is to identify the closest prior art, which may be closest to the invention in terms of structural features or in terms of the problem addressed. In practice, EPO Examiners will select the document based on which they think they can mount the best obviousness argument and there is little mileage in arguing that a document is not the closest prior art document since an invention is to be considered obvious if it is obvious over any document, not just the closest document. The second and third steps, which are somewhat intertwined, are to identify the technical effect achieved by the invention, as compared to the closest prior art, and the objective technical problem to be solved. These two steps are closely related since the objective technical problem must be solved by the features providing a technical effect and distinguishing the invention over the closest prior art. The final step is to determine whether the person skilled in the art would have applied the characterising features to solve the objective problem. In this stage there is often a lot of discussion of could or would, the point being that an invention is not obvious merely because the person skilled in the art could have applied the distinguishing features, there must also be some motivation to do that.

For inventions involving a mixture of both technical and non-technical features, or which solve a non-technical problem, the four step problem and solution approach is modified by the addition of an initial phase which has been referred to variously over the years but is now often referred to as the “requirements phase”. This concept was first introduced in the Comvik case (T0641/00 of September 2002). In that case the Board stated:

“where the claim refers to an aim to be achieved in a non-technical field, this aim may legitimately appear in the formulation of the problem as part of the framework of the technical problem that is to be solved, in particular as a constraint that is to be met.”

Since the non-technical aim or problem precedes the definition of the technical problem to be solved, it cannot contribute to the technical inventive step. Following Comvik, DunsLicensing (T0154/04 of November 2006) confirmed that the non-technical aim can be ascribed to the preliminary phase “even if it derives from an a posteriori knowledge of the invention”. In King Loan (T1284/04 of March 2007) the Comvik approach was justified on the basis that it:

“does not consider the non-technical constraints as belonging to the prior art, but rather as belonging to the conception or motivation phase normally preceding an invention since they may lead to a technical problem without contributing to its solution”.

Thus, the inventive step of a so-called mixed invention (that is involving both technical features and non-technical features or aims) becomes a five step process:

- Assign non-technical aims and features to the “requirements phase” irrespective of whether they are novel or not. Often examiners do this by copying the claim and striking out the non-technical features.

- Identify the closest prior art, in particular the document that is closest to the identified technical features. In some cases the EPO may have ascribed most of the features of the claim to the non-technical requirements phase leaving only generic technical hardware such as processors, memory and networks. In such a case, the Examining Division commonly asserts that such hardware is “notorious” meaning that it is so well known that there is no need to cite a specific disclosure.

- Identify the technical effect compared to the closest prior art. If at this point only notorious hardware is left in consideration, the Examining Division may directly object that the invention is obvious.

- Determine the objective technical problem, taking into account the closest prior art and features of the invention that distinguish it, in the same way as in wholly technical inventions.

- Finally, as with other inventions, decide whether the technical person skilled in the art would have employed the distinguishing features to solve the technical problem. Could/would considerations again apply.

One of the most contentious issues is what aims and features are to be considered as non-technical and technical. The concept of a “notional business person” is sometimes used to provide a more structured approach to addressing that debate.

The notional business person

The “notional business person” is a colleague of the person skilled in the art, introduced by Technical Board of Appeal 3.5.01 in T 1463/11 to give some objectivity to the process of assigning features and aims to being technical or non-technical. In the modified five step problem and solution approach, the job of the notional business person is to define the non-technical requirements which the person skilled in the art must then implement. The notional business person cannot contribute to inventive step; inventive step must be shown in the implementation of the requirements by the person skilled in the art.

The notional business person made his first appearance in two related decisions given on 29 November 2016 in appeals by CardinalCommerce against rejection of a parent and a divisional (T1463/11 and T1658/15). In these decisions, which have essentially identical reasoning, the Board recognised the need to analyse carefully the division between technical and non-technical features of a claim. The Board of Appeal introduced the “notional business person” and described what he/she does as follows:

“in the assessment of inventive step, the business person is just as fictional as the skilled person of Article 56 EPC. The notion of the skilled person is an artificial one; that is the price paid for an objective assessment. So it is too with the business person, who represents an abstraction or shorthand for a separation of business considerations from technical.

Thus, the notional business person might not do things a real business person would. He would not require the use of the internet, wireless, or XXXX processors. This approach ensures that, in line with the Comvik principle, all the technical matter, including known or even notorious matter, is considered for obviousness and can contribute to inventive step.

Similarly, the notional business person might do things that a real business person would not, such as include requirements that go against business thinking at the time – a sort of business prejudice, as is alleged in this case. If this were not the case, business requirements would need to be evaluated and would contribute to inventive step, contrary to the Comvik principle.”

Thus, the requirements must not specify or prohibit technical features but may include innovative business concepts.

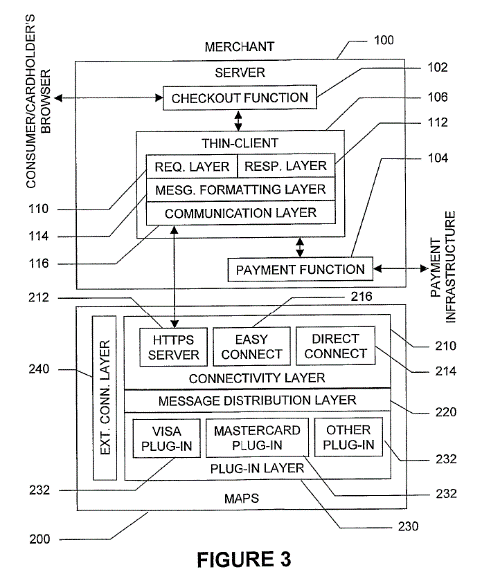

To illustrate this, it is worthwhile considering the invention of the CardinalCommerce cases. This related to e-commerce and specifically to websites through which goods or services are to be sold. In order to take payment, a merchant operating such a website needs to communicate with different payment servers in order to allow different forms of payment, such as credit cards, store cards or services like PayPal. According to CardinalCommerce’s inventions, an intermediary server is provided which deals with the different payment servers. The merchant therefore only needs to maintain one “plug-in” to interface with the intermediary server and not many separate plug-ins to deal with the various servers of the various payment providers.

CardinalCommerce advanced a variety of reasons why the person skilled in the art would not relocate the plug-in to support inventive step. Statements from four experts were submitted in support their arguments. The Board of Appeal divided the reasons put forward in to technical reasons and business prejudices. The technical reasons why the person skilled in the art would not have considered relocating the plug-ins included the potential for an increase in latency, possible reductions in the rate of processing transactions and an increase in the number of points at which communications could be subject to hacking. The Board considered that these reasons were sufficient to recognise an inventive step.

The business prejudices, which the Board of Appeal disregarded, included a loss of control by the merchant and a possible loss of profits to the third party operating the intermediary server. These issues are ones that the notional business person would consider and the notional business person is not to contribute to inventive step.

It is also worth mentioning that much of the evidence of the witnesses was disregarded by the Board of Appeal. The Board of Appeal considered that three of the witnesses, though having technical qualifications, were mostly giving evidence from the point of view of a business person and mostly addressed the commercial prejudices against relocating the plug-ins. In addition, much of the evidence was said to address specific embodiments rather than the generality of the claims.

It was not long before an applicant sought to use the CardinalCommerce decisions to a) overturn rejection of an invention for lacking a sufficient technical inventive step. In Gaming Server/Waterleaf (T0630/11) the applicant sought to argue that the Examining Division had erred in their apportionment of features to the non-technical requirements because they had included in those requirements features that had “technical implications”. The Board of Appeal thought that this went too far. They summarised their own earlier decision as follows:

“In CardinalCommerce, the Board stated that the notional business person (more generally, the non-technical person) cannot normally require even notorious technical means. The reason is that the inventor may have obtained a technical effect using technical means, even notorious means, in a way that would not have been obvious to the skilled person. That is what a patent is meant to reward. To allow the notional business person to prescribe technical means would be to foreclose any discussion of whether they were used in a technically non-obvious way. This should not lead to a proliferation of patents for technically trivial inventions; they would be obvious to the skilled person.”

And then went on to say that this did not mean that the notional business person was not allowed to include in requirements anything that had technical implications. The Board justified this with the example of a reader desiring a second copy of a particular book. The Board noted that to fulfil this desire would have technical implications because to do so the person skilled in the art would have to print a physical copy of the book or generate an electronic book. However, as long as the notional business person in setting the requirement does not prohibit or require specific technical means, the notional business person has not gone too far. Putting this in more claim-like language an appropriate non-technical requirement might be “provide content to a user” whereas an inappropriate requirement, involving technical subject matter, would be “provide content to a user in E-pub format”.

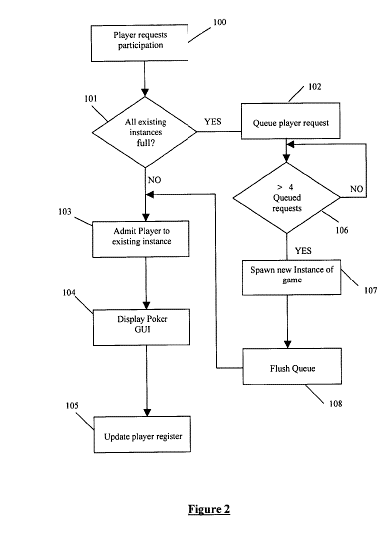

Again it is instructive to consider this in the context of the alleged invention of Waterleaf. The case related to online casinos running multiplayer games such as poker. In a casino, each instance of such a game has a minimum number of players and also a maximum. If a new player arrives when all current games are full, the player has to wait until sufficient additional players arrive to make up a game. The idea of the Waterleaf invention was that multiple online casinos would pool their waiting players so that a game could be started more quickly. The Board considered this to be a non-technical idea and ascribed it to the requirements phase:

“[the business person] can formulate the request to allow the waiting users of several casinos to play together without any understanding of what technical issues that would involve”.

Therefore, the Board recognised no inventive contribution from this idea. The claims specified a straightforward implementation of that basic idea using little in the way of technical language. An example claim feature is:

“an administration facility operable to legislate access at any time to any instance of the game by any would-be player requesting participation in the game, as a function of a number of players currently participating in that instance of the game”.

Therefore, the application was rejected as lacking an inventive step.

Thus, between CardinalCommerce and Waterleaf we have the rule that the notional business person must formulate requirements setting out the non-technical aims and features of the invention without using technical language and without requiring or prohibiting specific technical features. However, it is appropriate that the non-technical requirements may have technical implications.

At this point it is worth noting that the different technical Boards of Appeal of the EPO are not always consistent with each other, though generally converge eventually. Thus, whilst the CardinalCommerce and Waterleaf cases were heard by Board 3.5.01, Board 3.5.03 in Automatic selection of a home agent/QUALCOMM (T2328/13) overruled the Examining Division’s rejection of an invention for lack of inventive step because the claimed change would have “technical consequences”. In this case, the Examining Division had considered that changing which network entity performed the selection of a “home agent” for a mobile station (e.g. a phone) was merely “a business policy decision as it is not imposed by technical limitations”. However, the Board considered that it

“is not just related to a business policy decision, since in a mobile network there will clearly be technical consequences, for example concerned with hand-over from one base station to another”.

The QUALCOMM case however does not have any detailed elaboration of this point so we are left unsure how to distinguish between technical implications, whose presence would not prevent a feature being disregarded, and technical consequences meaning that a feature should not be disregarded in consideration of inventive step. Perhaps it is the case that a technical consequence is more immediate, specific or inevitable than a technical implication.

As a further example of the evolving nature of EPO case law, other Boards, and Boards 3.5.01 in a different composition, have previously discussed the role of non-technical people in the formulation of inventions, but without formalising that process. For example:

T0767/99 (System for Processing Mail/Pitney Bowes) of 13.3.2002 – 3.5.02

“the skills exercised in solving the problem addressed by this invention are those of a person skilled in the art of mail sorting, not those of a manager or businessman.”

T0172/03 (Order management/RICOH) of 27.11.2003 – 3.5.01

“It would be inconsistent with the terms and objects of the EPC to attribute an essentially different professional competence to the ‘person skilled in the art’ within the meaning of Article 56 EPC, for example by construing this term to include business experts or practitioners in other non-technological fields.”

T1000/08 (Advertisement selection/SONY) of 14.10.2009 – 3.5.01

“a business man getting the idea to select advertisements according to the requirements of commercial sponsors, content providers and individual subscribers, would hardly have turned to a programmer for developing this concept.”

T1321/11 (Authenticating an accessory/APPLE) of 4.8.2016 – 3.5.06

Authorisation scheme making use of parallel processing capability of device “would not have been formulated by the notional ‘businessman’ or ‘administrator’.”

T 2626/18 considered the possibility of a third person on the team alongside the skilled person and the business person, and rejected this idea, holding that each feature must be judged to be either the contribution of a technical expert or a non-technical business person.

Business person or person skilled in the art

If the distinction between non-technical requirements, which do not contribute towards inventive step, and technical features, which do, is to be based on the division of labour between the notional business person and the technical person skilled in the art it is desirable to clearly distinguish between these persons. The comments in CardinalCommerce and Waterleaf, and in particular the Board of Appeal’s criticism of the experts advanced in the former cases, suggest that a business person might be somebody with an MBA and a job title including words like account, administrator, finance, manager, financial analyst, process analyst. Examples of possible roles that the skilled business person might have include an insurance expert (T 0288/19), a psychologist (T 0344/19), a TV station manager (T 1117/19) and a real estate agent (T 2295/18). On the other hand, a technical person would be described as an engineer, scientist, programmer or potentially mathematician. Of course, there will always be some grey areas and for example a systems analyst has been implied to be a technical person in T0754/09 but to not be technical in T2048/07. T 3044/19 states “although technically skilled, the system administrators in this scenario are human beings performing the mental act of administering the computer system.”

Further clarification of the CardinalCommerce approach can be found in T 0909/14, which related to discriminating between two groups of users by providing them with different functionality. The decision set out the test to be used when deciding the technicality of a feature as whether the notional business person could have come up with it. The test requires only that there be at least one way to devise the feature without technical considerations, regardless of alternative technical ways of arriving at the feature being conceivable. Therefore, although there were technical reasons to limit the functionality of some users, there are also apparent business reasons for doing so.

Although not directly relevant, the EPO requires attorneys to have a technical qualification and specifies those degree subjects that are considered suitable: biology, biochemistry, chemistry, construction technology, electricity, electronics, information technology, mathematics, mechanics, medicine, pharmacology and physics. Thus, one could argue that a requirement is technical and should contribute to inventive step if to specify and implement it requires a person with one of the preceding qualifications.

One important point is that, just because a feature falls within the domain of a technical person, that does not mean that the feature itself is technical, as that person may also work on non-technical tasks. One example of this comes from T 0755/18, where it was held that computer programming includes technical and non-technical aspects, and so the fact that the program features were formulated by a software expert would not be enough to conclude those features were technical.

Examples of non-technical requirements that Boards of Appeal have excluded from consideration of inventive step include business methods, financial and transactional processes, legal requirements, policies (especially security and IP rights management policies). In cases relating to user interfaces, especially GUIs, an aim of making the interface easier to understand is often advanced. The Boards of Appeal often refer to this as “lowering the cognitive burden” and regard it as non-technical. However, we will discuss further below approaches to presenting improvements in user interfaces in a way that is seen as more technical. Problems that are seen as technical and have the potential to contribute to inventive step often relate to improving reliability or security, improving speed of operations or minimising use of resources. In relation to user interfaces, reducing the number of steps required to provide an input or increasing reliability of input have been combined technical.

Successful arguments

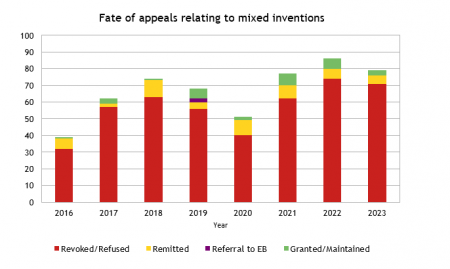

Based on the above, we will now consider some arguments that can be put forward to counter objections relating to non-technical subject matter as well as some considerations that can help at the drafting stage. However, it is first of all well worth noting that once an objection of non-technical subject matter has been raised the statistics do not encourage. Below is a graph showing, by year, the fate of appeal cases between January 2016 and October 2023 where some aim or feature of the invention has been considered to be non-technical. Almost 90% of cases are rejected (red) with only a small minority granted (green) or remitted to first instance for further prosecution (orange).

Whilst we have not carried out a detailed statistical analysis, there do seem to be different approaches between different examining divisions. Cases classified into IPC code G06Q seem to be rejected as non-technical almost by routine. Since classification of cases and allocation of them to examining divisions seems to be done on the basis of the abstract and first few paragraphs of the description, it is worthwhile setting a technical problem in these parts.

If an Examiner has asserted that the aims or features of an invention are non-technical, the first consideration is whether that assertion is correct. When such assertions are made, it is quite common for Examiners to overreach in their assertions as to what is non-technical. The CardinalCommerce and Waterleaf decisions discussed above can provide useful basis for arguing against the Examiner’s division of features between technical and non-technical. In particular, a common rebuttal is that the Examiner has employed technical terminology in his/her recital of the “requirements”.

It is also common for there to be dispute as to what is and is not technical. Again, the CardinalCommerce and Waterleaf cases can help. An argument that features are technical can be based on the fact that they would normally be specified and implemented by someone having technical qualifications.

In rare cases, it can be possible to have non-technical features taken into account in consideration of inventive step if they interact with technical features to achieve a technical effect. There are two cases citable on this point.

In Moving cache/Blackberry (T0117/10) a date range was used to limit calendar data being synced from an online database to a mobile phone. Although the specific date range used derived in large part from non-technical considerations, the Board of Appeal accepted that it nevertheless had a technical effect, in limiting data exchanges with the server, and hence needed to be taken into account in consideration of inventive step.

In Presentation of operating instruction/GAMBRO (T0336/14) the Board of Appeal said “in the assessment of whether or not a feature provides a technical contribution, the features shall not be taken by itself, but its technical character shall be decided by the effect it brings about after being added to an object which did not comprise that feature before”. This case concerned a blood treatment apparatus and the invention sought to solve the problem of enabling the machine to be set up in a safe and efficient way. However, the Board of Appeal considered that the distinguishing features of the invention did not contribute to setting up the machine safely and efficiently and hence could not contribute to an inventive step. Thus, this case further illustrates that having established a technical aim, it is essential to ensure that the distinguishing features of the invention contribute to the solution to that aim.

A commonly advanced argument for inventive step of inventions in the software field is that the invention is faster or more efficient than the prior art. Although improvements in speed and efficiency are good indicators of a technical effect, it can be difficult to establish such an improvement to the satisfaction of the Examiner. It is rare that directly comparable data is available and, even where it is, it has often been rejected on the grounds that it is not possible to establish that any improvement is due to the invention rather than better optimisation of code. Thus, to support claims of improved speed and/or efficiency it is best to point to specific steps or resources that are no longer required. Examiners, and Boards, will also often disregard claimed efficiencies as mere by-products of business decisions so it is important to show that an advantage derives from technical design choices. Examples of this include a reduction in network traffic due to alleged better recommendations of applications to a user in T 1983/18, or a reduction in user burden due to clustering of photographs being the inevitable result of implementing a non-technical scheme in T 1988/20.

When it has been established that inventive step of a software invention lies in the implementation of a solution to a problem, the question arises of what the person of ordinary skill in the art is capable without inventive effort. In a few cases, Boards of Appeal seem to have ascribed quite a high level of ability to the programmer of ordinary skill in the art. T2518/10 held that trade-offs between space and time are common place in computing and so it was not inventive to save time by storing a pre-rendered version of a chart in a document, rather than just the data on the which the chart was based, at the cost of increasing the amount of data needing to be stored.

In Decision T1126/13, the Board of Appeal characterised the invention as good programming in that it simply ensured that all messages were appropriately handled. T1534/14 held that a choice of programming language (Java applications vs native applications) was within the ordinary competence of the person skilled in the art.

User Interfaces

User interfaces, especially GUIs, have the additional issue that features may be disregarded as relating to mere presentations of information. This primarily occurs when an invention is characterised by the specific information that is presented and it ought to be possible to protect how something is presented rather than the specific information that is presented. Where the information to be presented is, or relates directly to, the internal state of a machine, then that can also be allowable.

However, UI inventions are often said to address the problem of making information, or an interface, easier for the user to understand. The Boards of Appeal generally refer to this as “reducing the cognitive burden” and consider it not to be a technical task. However, it is often possible to express the problem addressed by such inventions in a way that is more likely to be accepted as technical. In particular, Boards of Appeal have frequently accepted as technical inventions which enable a more reliable input or control or that reduce the number of interactions that the user must perform (T0063/12 and T1779/14).

Another approach is to link the invention to technical features of the display. For example, T0477/12 held that it was a technical problem to present information in a default format if that reduced processing (because a user would usually accept the default format) but not if it was simply intended to make it easier for the user to appreciate how different formats would look.

Another common argument is that an invention addresses technical limitations of a device, most commonly limited size or resolution of a display (e.g. T2028/11). For this argument to succeed, it is essential that the claims of the invention are limited to the display that exhibits the limitations being overcome.

Simulations

In recent years, the patentability of simulations has become more and more relevant. Simulations of technical systems were generally considered to be technical, but the Enlarged Board Decision G1/19 (Pedestrian simulation) has focused attention on the ultimate purpose of a simulation as much as the nature of the system being simulated. Whilst the Enlarged Board held there is no requirement for a link to physical reality to provide a technical effect beyond the implementation of the simulation on a computer. However, the simulation being based on technical principles underlying the simulated system or process is not sufficient to provide a technical effect, meaning that simulating a technical system does not provide technicality. Equally, claiming the simulation as part of a design process does not make a difference. In T 1453/17, the Board of Appeal held that G 1/19 only confirmed the Comvik approach, and that the assessment of technicality was to be decided by the Board for each individual case.

One important point to be taken from G 1/19 is that, although not required, a direct connection between a simulation and reality is a strong indicator of technicality and can allow for features that are non-technical in isolation to be included in the assessment of inventive step. This can be seen in T 1892/17, where simulations of electrical power consumption by individual users were used to control actual apportioning of the electric power to individual consumers. Another point made by G 1/19 was that establishing a model of a system is a non-technical mental act. T 2014/21 expanded on this to include improving a model as also being a non-technical problem.

It was also held in G 1/19 that technical character can come from the technical use of an output. In T 0199/16, the Board held that, where the technical use of the output is relied on, non-technical uses must be excluded so that the whole breadth of the claim is technical. Therefore, a method for calculating a “usage fee” for leasing a vehicle was non-technical, since the usage fee clearly had business usages and so was not technical over the entire scope of the claim. For this same reason, the application that led to the G 1/19 referral was refused in T 0489/14, as the output of the invention was not limited to technical uses. Similarly, in related cases T 2594/17 and T 2607/17 the inventions related to a training simulation of virtual weldments. As the only output was a pass or fail judgement, not of the weld but of the welder’s skill, the applications were refused due to a lack of a technical use.

Security

There have been many cases relating to inventions addressing security of software and networks. This is generally accepted as being a technical field but the Boards of Appeal have sometimes considered vague references to spam or malware as non-technical since at one level these are just messages or programs that are undesired. It is also important to ensure that the invention does achieve an identifiable increase in security without manual intervention. In T1307/15 the Board of Appeal considered many features of the invention not be inventive because an increase in security was only achieved if certificates identified by the invention as potentially bad were manually revoked.

Another fine distinction that needs to be drawn is to ensure that the invention does not relate to a security policy (e.g. that a user can only read their own department’s documents) but lies in the technical implementation of that policy (T0119/11). On the other hand, Boards of Appeal have recognised a form of problem invention in this area, holding in T0832/14 that if an attack vector was not known, a defence against it would not be obvious.

Often, security related inventions require or involve two different users. Often, the users are referred to as an administrator and a user. However, such terminology can be distracting and Boards or the Examining Division may consider the difference between an administrator and an ordinary user to be a non-technical one. This can be avoided by referring to the users as a first user with a first set of privileges and a second user with a second, different set of privileges.

Games, AR & VR

There are also common themes in the area of games, simulation and augmented or virtual reality. In T0339/13 the Board held that to increase user engagement, as a general aim, was not technical. However, to increase realism, for the purpose of increasing user engagement, is technical. This can be a fine line to draw.

Inventions in this area which involve a connection to the real world, or to the need to present events in real time are generally regarded as technical. T1554/10 held that it was a technical problem to adapt an object in an augmented reality preventative to better reflect real-world circumstances.

As mentioned above, it has frequently been accepted that to present information relating to the present state of a machine is a technical problem. However, the Boards have drawn a distinction between indicating state of the machine and the state of an application running on the machine. If the latter is a game or a business process tool then the Board does not consider it to be technical. An exception to this exception was however found in Video Game/Konami T0928/03 where the Board considered that addressing a problem in signalling a game state that was caused by technical issues, e.g. display limitations, was a technical problem.

Equally, methods that could be carried out by a person, such as a trainer, are not considered to be technical. An example of this is T 2689/18 which related to a method of measuring crew member communication skills. As the parameters used involved administrative, psychological and mental acts, and the rating provided had no technical meaning, the method was considered to be non-technical.

Summary

At the EPO, for inventions involving non-technical features or aims as well as technical features, the non-technical features cannot contribute to inventive step. The normal four-step problem and solution approach to inventive step is therefore modified by an initial step of assigning non-technical features to the “requirements phase”. The requirements phase is performed by a notional business person who must not use technical language and must not prescribe or proscribe specific technical features to implement the requirements. The implementation is done by the technical person skilled in the art and any inventive step must lie in that implementation.

To maximise the chances of grant, it is important to emphasise the technical features of the invention and to put forward a technical problem, ideally in the opening of the application. If an assertion that claim features are non-technical is raised, it can occasionally be argued that the non-technical features combine with technical features to achieve a technical effect but that is hard to justify. It is always important to ensure that the claims are limited by technical features that directly solve a technical problem.