Review of EPO Antibody Decisions in 2022

Last year we provided a review of 17 EPO Board of Appeal cases relating to “antibody inventions” that were decided between January and December 2021. We noted that this number had increased from our previous analysis, suggesting that the trend of minimal case law concerning antibodies may be reversing.

We have now reviewed the decisions published in the calendar year of 2022, and we observe that there has been a further increase in the number of Board of Appeal decisions relating to “antibody inventions”. The total was 19 decisions for the year.

We do not believe that any of the 19 decisions covered in this review represents a significant shift in EPO practice, nor that any of them will compel changes in the way examination is conducted. Rather, the EPO largely continues the trend that we observed last year, in that antibody inventions are treated no differently to any other forms of technology. In decisions where “antibody-specific” considerations may be applied, the EPO has done this consistently and in line with the (now largely established) basic principles that are further explored in our advanced guide to drafting and prosecuting antibody inventions at the EPO. The majority of the decisions support the current practices of the Examining Divisions that we observe in routine prosecution, and which were partly codified in a dedicated section of the EPO’s Guidelines for Examination (G-II, 5.6; issued March 2021 and revised in March 2022 – also discussed in our advanced guide).

On a day to day basis the Guidelines may therefore remain a more significant source of guidance than the case law, but the 19 decisions covered in this review nonetheless provide confirmation and consolidation of EPO practice, represent useful examples of fact patterns for future reference, and may also help to illustrate developing trends. As we noted above, one of these trends is the continued increase in Board activity in the field of antibody inventions. In addition, we see an increase in the proportion of cases relating to “downstream” developments of existing antibodies, particularly in treating subgroups of patients. Lastly, we have seen some evidence over the year that the EPO is still willing to allow broad “anti-target” antibody claims under certain circumstances. These trends are encouraging for applicants who may have been forced to accept relatively narrow, structurally-defined antibody claims in the USA and are looking to obtain broader coverage Europe.

We previously predicted that we would see more attempts to claim an antibody “sub-class” to provide some breadth around one or more specific antibodies. Such cases may define a sub-class by comparison to a specific antibody, using terms such as “competes for binding”. This type of definition is narrower than a claim directed broadly to an “anti-target” antibody, but it provides greater coverage than claims which define the antigen binding domains or complementarity-determining regions (CDRs) by their specific amino acid sequence. Although we have not seen any decisions in 2022 relating to an antibody sub-class, we think applicants will still be interested in trying to claim antibodies in this way. We expect to see Board of Appeal decisions on this point in the future.

Below we provide some statistics from the 19 decisions and discuss some of the more interesting cases in detail.

Statistics

We identified 72 decisions published between 31 January 2022 and 31 December 2022 and which refer to the term “antibody”. 53 of these decisions were not directly concerned with antibody inventions as such and so are not considered further in this review. Of the remaining 19 decisions, 15 concerned appeals from Opposition Division decisions, and 4 concerned appeals from Examining Division decisions. Board 3.3.04 retained its position as the most prolific “antibody Board” with 16 of the 19 decisions (previously 12/17 in 2021). 2 decisions were issued by Board 3.3.08 (previously 4/17 in 2021), with the final 1 decision issued by Board 3.3.01. We identified no antibody decision by Board 3.3.07 (previously 1/17 in 2021). We discerned no obvious differences in practice between the various Boards.

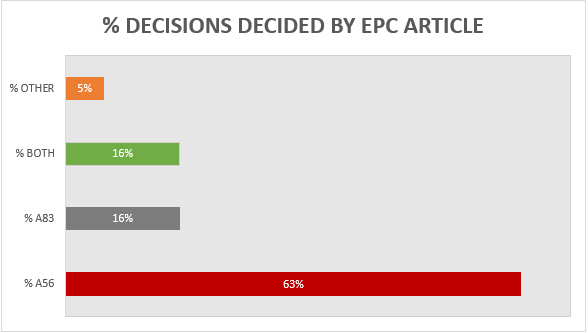

A breakdown of the key grounds for each decision is provided in Figure 1.

Figure 1

Building upon the trend from previous years, more than 60% of the 19 decisions were decided primarily on the basis of inventive step (Article 56 EPC), with a slightly increased proportion (16%) decided primarily on the basis of sufficiency (Article 83 EPC), and 16% considering both inventive step and sufficiency to some degree. It remains the case that there is often considerable overlap between Article 56 EPC and Article 83 EPC for antibody inventions, and we found the EPO’s assessment of both Articles to be consistent across all of the relevant decisions. Outside of Article 56 and 83 EPC, only 1 decision was decided on another ground. This decision was T 2900/18 and the ground was Article 54 EPC (novelty). Specifically, claim 1 related to an inhibitory anti-IL-6 antibody for use in the treatment and/or prophylaxis of glomerulonephritis associated with a vasculitic disorder. The prior art disclosed an identical antibody for use in the treatment of glomerulonephritis associated with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), so novelty depended on the interpretation of the claimed condition. The Board held that “associated with” would be interpreted as “linked to” and vasculitis was considered to be linked to SLE. The claims were therefore rejected for lack of novelty and the patent was revoked.

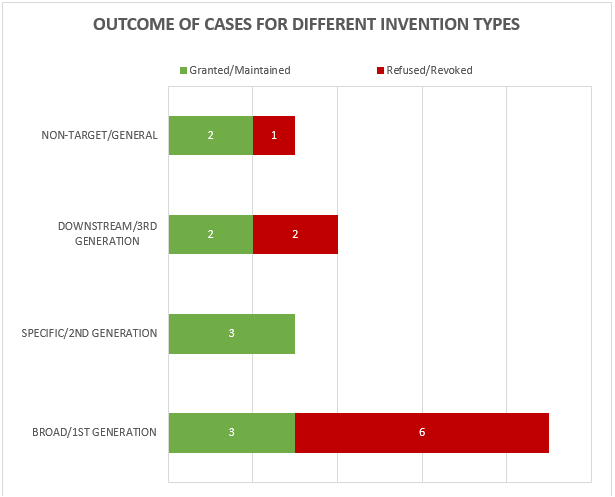

The 19 decisions can also be divided into 4 general categories of invention as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2

This year the largest category (9 decisions – 3 granted/maintained, 6 revoked/refused) is concerned with what we define as “broad” anti-target antibody inventions. The earliest form of application/patent in this category is sometimes described as a “1st generation” antibody case. Such cases may entirely lack disclosure of any individual antibody molecule that binds to the target, especially if the invention relates to the identification of the target and/or a link to a particular indication, rather than to an individual antibody or antibodies. The backlog at the Boards of Appeal means that there are likely some cases of this type still to be decided.

The next largest category (4 decisions – 2 granted/maintained, 2 revoked/refused) is concerned with what we define as “downstream” antibody inventions. These inventions relate to advances which typically arise during downstream development of a pharmaceutical, such as combinations with other therapeutic agents, or identification of alternative medical uses, subgroups of patients, dosing regimens, partner diagnostics, and the like. In many respects these are not specifically “antibody inventions” because the target binding properties of the antibodies concerned have usually already been established in the art. We find that such inventions are examined by the EPO in the same way as comparable inventions for non-antibody pharmaceuticals. We identified no particular trends in the spread of positive and negative decisions for the applicant/patentee in this category in 2022. We expect a steady number of decisions relating to downstream developments in the future.

The next category (3 decisions – 2 granted/maintained, 1 revoked/refused) is concerned with antibody inventions that we define as “non-target” or “general” in nature, and is similar to the above in that inventions in this category are not typically subject to any “antibody-specific” considerations. Rather they are examined in broadly the same way as any other technology at the EPO. Also similar to the above, we do not see any particular trends in the spread of positive and negative decisions for the applicant/patentee in this category, but it is pleasing to see that general antibody platforms, such as antibodies with modified Fc regions, remain patentable at the EPO.

The final category (3 decisions – 3 granted/maintained) is concerned with what we define as “specific” or “2nd generation” antibody inventions. Typically the invention relates to an individual antibody or antibodies, defined by sequence, and directed to a well-characterised target for which prior art antibodies (often therapeutic antibodies) are known. Readers are likely familiar with the EPO’s approach to such inventions. All antibodies specific for a target are obvious by comparison to prior art antibodies for the same target, unless an unexpected effect is plausibly demonstrated. This can be particularly challenging when the prior art includes high-affinity therapeutic antibodies to the same target. Consistent with the trend from last year, all of the decisions in this category featured Article 56 EPC (inventive step) as a key ground. Perhaps surprisingly, the antibodies in each of these cases were held to be inventive. Experimental data is often essential for demonstrating inventive step and in one of the cases the proprietor relied on data comparing the affinity of the claimed antibody with that of the prior art, which the Board relied on in their decision. As mentioned last year, despite the large number of “specific” antibody inventions prosecuted at the EPO, there tend not to be many Board of Appeal decisions relating to this category. This may be because the relatively narrow scope of the claims is less likely to be subject to opposition. Indeed, 2 out of the 3 decisions in this category are appeals from the Examining Division.

Broad/1st Generation Decisions

T 1964/18 (Inhibitory anti-NKG2A antibodies/INNATE) concerned an anti-NKG2A antibody which was functionally defined by its epitope. The prior art disclosed the sequence of an anti-NKG2A antibody, but this antibody was found to bind NKG2C and NKG2E as well as NKG2A. The Board held that it was inventive to modify the prior art antibodies such that they only blocked the activity of NKG2A and not NKG2C and NGK2E, in order to improve the activation of Natural Killer cells. This decision therefore provides further evidence that the EPO will permit “genus” antibody claims under certain circumstances, without requiring specific antibody sequences. Interestingly, the corresponding US patents in the same family faced objections of insufficiency, and the granted claims were limited to the specific hybridoma or antibody CDR sequences.

T 1911/17 (BNP(1-32) epitope specific antibodies/BIORAD) also sought to claim an antibody which was broadly defined by binding to a specific epitope on Brain Natriuretic Peptide (BNP) (1-32). The proprietor argued that the claimed antibody had improved effects compared to an antibody for the same target disclosed in the closest prior art. Based on a lack of evidence on file, the Board could not conclude that the claimed antibody was superior to the prior art antibody in recognising the epitope. It was therefore held to be an obvious alternative.

T 2416/18 (Cross-neutralising antibodies/POMONA RICERCA) claimed a functionally defined antibody supported by a single Example in the patent specification. Considering the requirements for sufficiency under Article 83 EPC, the Board held that identifying a single antibody with a particular property was not enough to claim any antibody having that property, because there were doubts that the methods described in the specification would reliably identify more candidates. This decision is in accordance with standard practice at the EPO and reinforces that the antibody field is generally not treated differently to any other forms of technology.

T 0317/20 (NGF antagonist for treatment of osteoarthritis/RINAT) concerned an anti-NGF antagonist antibody for improving physical function in osteoarthritis patients. During opposition proceedings, the opponent argued that the reason physical function was improved was because pain was being relieved, so this meant that the invention was not enabled for a subgroup of osteoarthritis patients who do not experience pain. The Board held that the lack of precision in the definition of the disease being treated meant that the claim encompassed this subgroup of patients, and thus the effect of “improving physical function” could not plausibly be expected to occur in all patients. The patent was subsequently revoked. The substantive issues discussed in this case are not unique to antibody inventions, and as such it provides more evidence that applicants are keen to pursue the same types of downstream invention for antibodies as they do for other medicines. Similarly, it supports our assertion that the EPO do not generally treat antibodies differently to other types of pharmaceutical.

T 0921/17 (Bispecific antibody/CHUGAI) concerned a bispecific antibody that can functionally substitute for coagulation factor VIII, comprising a first binding domain that recognises coagulation factor IX and a second binding domain that recognises coagulation factor X, with a commonly shared light chain. The patent proprietor successfully argued that the claimed bispecific antibody was novel because the concept of a commonly shared light chain was not directly and unambiguously disclosed in the prior art, which concerned a bispecific antibody having the same targets. Nothing in the decision is particularly specific to antibodies, but may be of interest in that broadly defined bispecific antibodies can be obtained at the EPO under certain circumstances.

Specific/2nd Generation Decisions

T0505/19 (VCAM-1 antibody/OXFORD UNIVERSITY) related to humanised anti-VCAM-1 antibodies for use in in vivo imaging applications. The claimed antibodies were non-neutralising and low affinity. The prior art disclosed neutralising non-human anti-VCAM-1 antibodies with higher affinity. The Board held that the skilled person would not have modified the affinity of the known antibodies and so it was decided that the claimed antibodies were inventive. The Board agreed with the appellant that the claimed antibodies would be advantageous for imaging in humans.

T 2589/16 (Cross-species CD3 antibody/AMGEN) concerned a bispecific polypeptide comprising an anti-CD3ε binding domain and a second binding domain capable of binding to a cell surface tumour antigen. The claim was limited during proceedings to the specific CDR sequences of a particular anti-CD3ε antibody, which were considered to be novel and inventive. The broadly defined second binding arm was held to be sufficiently disclosed, because there was no evidence that the skilled person would be unable to identify domains capable of binding to a cell surface tumour antigen. This suggests that in a bispecific format, the EPO may only require one of the antigen binding arms to be structurally defined, provided that part of the molecule is novel and inventive. In this case, it was possible to claim a broad, functional definition for the other antigen binding arm.

T 1171/18 (Humanised biotin-antibodies/HOFFMANN-LA ROCHE) concerned humanised anti-biotin antibodies which were defined by specific heavy chain and light chain variable region sequences. The prior art disclosed the murine antibody from which the claimed humanised antibody had been derived. The Examining Division had rejected the claims under lack of inventive step, because they considered the humanisation of a known antibody to be obvious. However, the Board disagreed with the Examining Division and held that there was an unexpected effect arising from the specific humanised sequences of the claimed antibody, in that the binding affinity for the target was largely maintained relative to the starting murine antibody. This case suggests that a humanised version of a known antibody could still be inventive under some circumstances, if it can be argued that the specific outcome of the humanisation process results in some surprising property.

Downstream/3rd Generation Decisions

T 2214/17 (PCSK9 E670G mutants/KYMAB) concerned an attempt to define a subgroup of patients for treatment with anti-PCSK9 (evolocumab) based on the presence of specific PCSK9 variant and a particular heavy chain allotype. No evidence of improved treatment in the subgroup was provided. It was held to be obvious to treat the subgroup because (i) the PCSK9 variant was physiologically active, so it was reasonable to expect evolocumab to bind it (unlike other inactive variants which evolocumab does not bind) and (ii) it was obvious to match the allotype of a therapeutic antibody in order to minimise anti-drug immune responses in the patient. This is broadly consistent with EPO practice relating to patient groups treated with other types of pharmaceutical.

T 1759/17 (Evaluation of immune response to therapeutic protein/BIOGEN) related to a method for detecting a clinically significant response to natalizumab. The general principle of the invention is the distinction between “transient” and “persistent” patients. The patent was maintained because the Board found that ambiguity at the edges of the claim (in regards to the threshold level of detected antibodies) does not in general lead to a lack of sufficiency. This case is further evidence that downstream inventions associated with antibodies can be protected at the EPO in the same manner as for other therapeutics. We expect to see increasing numbers of patent applications directed to such downstream developments in the antibody field.

T 0975/16 (LAG-3 on regulatory T cells/JOHNS HOPKINS) concerned a combination of an anti-LAG-3 antibody and an anti-cancer vaccine comprising isolated tumour antigens, for use in treating a subgroup of cancer patients characterised by the presence of regulatory T cells which suppress an immune response in response to the vaccine. The combination in this case was held to be inventive based on the (minimal) data in the specification, which show that LAG-3 is expressed at higher levels on immunosuppressive regulatory T cells present in the newly identified patient subgroup. The antibody / vaccine combination would therefore function differently in this sub-group, leading to an unexpected, advantageous technical effect. Again this is broadly consistent with EPO practice relating to patient groups for other types of pharmaceutical. It is a clear demonstration that the EPO will allow patents for downstream developments of a pre-existing antibody.

Non-target/General Decisions

T 0424/21 (Antibody Fc variants/ROCHE GLYCART) related to a modified Fc region having reduced ability to activate antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity (ADCC). The granted claims covered a broad genus of antibodies defined by specific mutations in their Fc region. The Examples of the patent only provided data for specific antibodies, so the opponents had argued that the antibodies were not sufficiently disclosed over whole scope of the claim. These arguments were dismissed by the Board because there was no evidence that the claimed effects were restricted to the particular antibodies used in the Examples. This case shows that broad antibody “format” claims can be obtained at the EPO. T 0784/19 (Canine immunoglobulins/ZOETIS) is another case where antibody “format” claims were held to be allowable at the EPO. The claims related to specific heavy chain constant domain sequences which minimised the activation of downstream immune system effector function when the antibody is bound to its antigen.

In contrast, the Board revoked the patent in T 2164/21 (Method for producing a stabilised antibody/CHUGAI), which concerned a method of producing an antibody with reduced susceptibility to deamidation. The alleged invention involved substituting a glycine residue adjacent to an asparagine residue in CDR2 of the heavy chain of an antibody. The prior art disclosed that deamidation of asparagine is generally facilitated if the side-chain of the subsequent residue is small or absent, as in serine or glycine. The Board therefore held that it was obvious to replace either of these amino acids to avoid deamidation. The Board then considered auxiliary request 1, which introduced an additional requirement that the modified antibody retain at least 70% of the antigen-binding activity of the original antibody. It was found that neither the patent specification nor the common general knowledge provided the skilled person with sufficient information to reliably identify modifications that would retain the required antigen-binding activity. Accordingly, the Board found the auxiliary request to lack sufficiency.

Trends and Conclusions

Last year we found that the majority of the decisions identified related to inventions that were not directly concerned with the “target binding” properties of antibodies. That is, the inventions were either applicable to antibodies generally, or were downstream developments of a pre-existing antibody, the target-binding properties of which have already been established. This trend has not been maintained. This year, we saw 10 decisions that were specifically concerned with “target binding” as compared to only 7 decisions which are not target dependent. Nonetheless, it is reassuring to see that, once again, the Boards have approached all of the decisions discussed in this review in a manner which is consistent with the EPO’s treatment of other forms of technology, in particular other pharmaceuticals.

We suggest that there is a continued lack of interest in opposing patents in the specific/2nd generation anti-target category. We believe this explains why there are only 3 decisions in this category in the present review (2 of which are appeals from Examining Division decisions), despite this being the most common type of antibody claim that we observe in prosecution.

Finally, as mentioned above, we expect to see more attempts by applicants to claim a “sub-class” around a narrow antibody claim, to obtain a level of breadth somewhere between narrow claims defining the antigen-binding region by amino acid sequence and broad “anti-target” claims. Such claims are likely to be desirable for applicants who may already have obtained grant of narrow claims for their lead antibody, but would ideally like to capture some additional breadth for variants, perhaps via one or more divisional applications. Although we have not seen any decisions on this point in 2022, we anticipate that the Board of Appeal will be called to decide on such antibody “sub-class” inventions in the future.