Review of EPO Software Decisions in 2022

The Enlarged Board Decision G1/19 relating to simulations was the most significant event in the field of computer implemented inventions in 2021, but it is only in 2022 that its full impact has become apparent. Whilst initial expectations were that it would not be transformative since it primarily endorsed case law, it has resulted in an increased focus in the Boards of Appeal and Examining Divisions on ensuring that an invention meets the technicality criteria across the whole scope of the claims. As discussed further below this can result in rejections for failure to exclude non-technical uses of outputs of a method, for failure to achieve an advantage over the whole scope of the claim or a lack of clarity that any effect is achieved. There have also been a number of interesting cases relating to simulations and to computer implemented inventions in medical fields. These topics, as well as other cases of interest published in 2022, are discussed further below.

Statistics

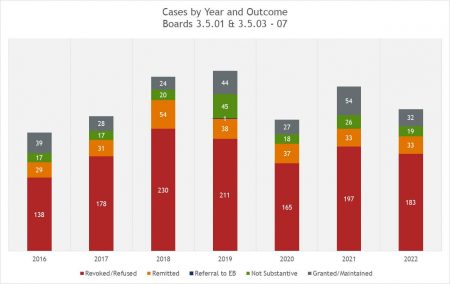

Looking at cases published in 2022 for Boards 3.5.01 and 3.5.03 to 07, we see no clear trend in number of decisions published. 267 cases in total is lower than 2021 but higher than 2020 and perhaps reflects the disruption caused by the Covid pandemic on the previous steady growth in decisions issued. Although we have not sought to collect statistics, it appears that many oral proceedings were conducted by video in 2022 and many not attended by the parties. Overall, the length of time taken for Appeals to be concluded seems to be growing and backlogs are increasing.

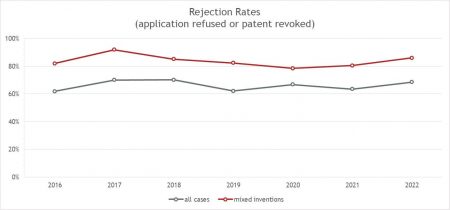

On the other hand, the Boards’ rejection rates remain reasonably consistent with over 68% of cases overall resulting in refusal of the application or revocation of the patent, increasing to 86% for cases involving some non-technical feature.

Whole Scope

An important point made in Enlarged Board Decision G 0001/19 (Pedestrian simulation) (discussed in our briefing here) is that the requirement for technical subject matter must be met across the whole scope of the claim, just as with other requirements for patentability. This requirement can be failed in several ways: a failure to exclude non-technical subject matter; a failure to achieve a technical advantage reliably over the whole scope; or a lack of clarity leading to lack of credibility that an effect is achieved. One consequence of the G 0001/19 seems to be an increased focus on these issues by Boards and Examining Divisions.

Failure to exclude

The need to exclude non-technical uses of an invention was highlighted by Board 3.5.01 in T 0647/20 (Produktionsleitsystem/PELZ). The invention at issue characterised problems in a production plant using a traffic light system to indicate how long a fault has gone unfixed, rather than the intrinsic severity of the fault. Since the time allowed to fix a fault before it is marked red could be set on the basis of business or economic considerations, the Board considered it to be non-technical, commenting “it is sufficient that a partial feature allows for a non-technical interpretation for it to be considered a non-technical feature” (emphasis added).

Board 3.5.07’s decision in T 1371/16 (Designing a wiring path/YAZAKI) seems quite harsh at first view. As the Board summarises the invention, it concerns “design of wiring paths of wire harnesses in a three-dimensional space such as a vehicle body. The design takes into consideration three-dimensional data of a body in which the wire harness is installed, a minimum bending radius of the wire harness which varies depending on a type and the number of wires to be bundled into a wire harness, and a type of the covering of the wire harness”, all of which seems very technical. However, the output of the method was “data on corrected wiring path data” with no limitation as to the form of the data or its subsequent use. Therefore the output data “cannot be considered to be specifically adapted for the purposes of an intended technical use. In particular, the output data is not specifically adapted to be used in controlling a technical device or manufacturing a wiring path” and “is not limited to a further technical purpose”, as required by G 1/19. It seems likely that a claim to manufacturing the designed wiring harness would have been allowed but none was advanced. Perhaps such a claim would not have had much commercial value since the final step of installing the wiring harness is perhaps performed by the appellant’s customers rather than their competitors.

Reliability

T 1900/18 (Ingredient-based product recommendation/SOUTHAM) (also discussed below in the section on medical inventions) was rejected in part because Board 3.5.01 had doubts that the effect put forward by the appellant, i.e. providing a better recommendation of products, would be reliably achieved. The description proposed an algorithm for deciding what product to recommend “based on the assumption that the effect of the ingredients is additive, i.e. that a product’s efficacy is proportional to the number and efficacy of its ingredients” but did not take into account the possibility of interactions between ingredients.

A user interface invention, T 1098/20 (Message user interfaces for capture and transmittal of media content/APPLE), was argued to provide simplification and reduction in the user input required to achieve the desired output, independent of any subjective user preference. However Board 3.5.05 observed that, while the single claimed interaction was fewer in number than the four touch interactions required in the prior art, it was a complex gesture making higher demands of the user. Thus whether one complex gesture is easier for a user than four simple ones is a subjective issue and so the “effects suggested by the appellant cannot be regarded as technical effects credibly achieved over the whole scope of claim 1”.

The same Board in T 0885/20 (Control system at an airport/ADB SAFEGATE) asserted that the invention did not increase “efficiency and safety at the airport” when an aircraft sending a signal was close to its gate. Hence the distinguishing feature was to be disregarded as “an arbitrary, non-functional modification of the prior art.”

An advertising invention in T 2363/19 (Content-item selection) was argued to save bandwidth and other computing resources through selective provision of visual-centric or audio-centric adverts depending on which type of media the user had previously been consuming. However, the Board rejected this argument, inter alia, as there was no guarantee that visual-centric adverts, which could be text, would require less resource than audio-centric adverts.

Clarity

The claims at issue in T 1560/19 (Monitoring equipment behaviour/BLUE YONDER) were rejected by Board 3.5.03 for an inherent lack of clarity, but in addition because no technical effect was credibly achieved. The Board considered that because the claims used ‘general terms such as “numerical transfer functions”, “input-to-output mapping” and “configuration”, which are inherent to any processing unit … the claimed data processing device acts as a “black box” using abstract mathematical method steps, without achieving any credible technical effect. In this respect, the board recalls that, according to Reasons 124 of G 1/19, “only those technical effects that are at least implied in the claims should be considered in the assessment of inventive step”.’

Clarity issues quite often arise in relation to methods involving several different users. An example is T 1777/18 (Monitoring vehicle locations/HEMBURRY). The appellant argued that the details of the involved parties were not relevant; it was only required that there were different entities. Board 3.5.03 however held that ‘the “authorized user” and the “applicant” are elements of claim 1 involved in the respective method steps and therefore need to be precisely determinable’. Thus, whilst descriptive names can make a claim easier to understand on first reading, it is often safer to use neutral terms to denote persons in a method (e.g. first user and second user) and explicitly define their characteristics (e.g. first user has read/write privileges, second user only read).

Simulation

It is also interesting to look at how the Technical Boards have such applied the Enlarged Board Decision in G 1/19 on patentability of such inventions.

Firstly, it is perhaps not surprising that in T 0489/14 (Pedestrian simulation/BENTLEY SYSTEMS) Board 3.5.07 refused the application that was the origin of the referral to the Enlarged Board. In summary, modelling pedestrians as elementary particles was not enough to confer technical character whilst the output of the invention, even after several limitations, was not limited to technical uses and still covered, for example, uses in games or for educational purposes. A link to measurements as the origin of data underlying the model was too remote. Claims to control of robots, which perhaps had the highest chance of being considered technical, were not admitted as they had not been pursued at first instance.

Failure to limit the output of a simulation to technical uses also resulted in the refusal of T 1035/18 (Estimating airborne photovoltaic energy production/BOEING) by Board 3.5.01. The output of the method was an estimate of electrical energy that would be generated by PV cells on an aircraft flying a specified route. In some requests, this was converted to an estimated fuel saving, which the appellant argued would result in refuelling with a reduced fuel load. However the Board noted that the refuelling step was not included in the claim and whether the generation of electrical energy is actually taken into account in determining a fuel load would be a decision for the ground crew. Therefore, the output of the method could be used for non-technical purposes, e.g. business decisions on the viability of a route or whether to install the PV system. The Board considered this situation to be a form of the “broken technical chain” that is a frequent ground of rejection of methods relating to presentation of information.

Staying with the aviation industry, T 2350/17 (Entwerfen von Flugzeugen/DEUTSCHE LUFTHANSA) was rejected by Board 3.5.01 even when construction of aircraft was included (in an auxiliary request) because “under no circumstances, however, is an aircraft with generally improved technical properties achieved by the invention, but only an economically optimized dimensioning”.

Another case of failure to limit the uses of the output of a simulation was T 2660/18 (Developing rod patterns in nuclear reactors/GLOBAL NUCLEAR FUEL-AMERICAS). Board 3.5.07 held that ‘no technical effect is achieved by the method’s functionality as the method merely produces a test rod pattern (i.e. a fuel bundle configuration) design and data “indicative of limits that were violated by the proposed test rod pattern design during the simulation”.’ They further commented that a “rod pattern design appears to have non-technical uses such as for study purposes”.

T 2014/21 (Simulation accuracy/YOKOGAWA) related to a simulation of an industrial plant and was found non-inventive on the basis of prior art and common general knowledge. Board 3.5.03 did make one point of general relevance: that since G 1/19 says establishing a model of a system is a non-technical mental act, then improving such a model is likewise not a technical problem.

The appellant in T 3226/19 (Opportunity estimation/LANDMARK GRAPHICS) tried to argue that the invention, relating to petrochemical prospecting, was a technical simulation but Board 3.5.07 rejected this. The calculations involved did not amount to a simulation because “no imitation of the operation of a system or a process was defined.”

T 1615/17 (Linking place information based on position/RAKUTEN) did not relate to a simulation invention, but one argument advanced was that the claimed invention was technical because it used technical data, specifically position data, which was one route identified in G 1/91 to showing technical character. Board 3.5.01 however rejected this argument because the “position information does not retain any technical character related to how it was measured in the subsequent data processing.”

Medical

The increasing level of development in digital health was reflected in 2022 Board of Appeal cases, with some Boards that do not usually handle software grappling with whether or not subject matter is technical.

For example, in T 1217/18, Board 3.2.02 considered claims directed to a “Device for monitoring access to a patient for an extracorporeal blood treatment” which differed from the prior art only in the conclusion drawn from a detected change in a characteristic of the patient’s blood (such as haemoglobin concentration). The invention at issue concluded that “vascular access is not proper” but the prior art warned of possible bleeding or excessive ultrafiltration. The Board held that the conclusion has no technical character in itself and claim 1 of the main request “neither defines that the conclusion is further used nor that it is reproduced. There is thus no interaction with other features of the claim which contributes to the technical character of the invention.” However, an auxiliary request that specified control actions to be taken automatically in response to the detected change was allowed.

T 0752/19 (Ticagrelor, acetylsalicylic acid and a computer program/INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY ENABLER STOCKHOLM) was an unusual case before Board 3.5.05 that concerned the combination of a medicament and a computer program that the patient interacted with. Use of the program was said to improve patient compliance with the medicine regime, which was argued to be a technical effect. However Board 3.5.05 held that patient compliance would be technical “only if it were shown to arise objectively in an unbroken technical chain from the intrinsic properties of the claimed pharmaceutical formulation”, as had been the case for inventions in which compliance was improved by formulation changes. The Board therefore did not recognise a “technical effect of improved patient compliance brought about by a computer program generating and presenting patient-specific feedback [that] is conditional on the patient’s mental activities”. Another argument was that the CE mark granted to the program was an indicator of its technical character but the Board considered that “regulatory approval of a device has no relevance to the assessment of its patentability in accordance with the EPC.”

The appellant in T 1743/19 (Possible next actions/CAREFUSION303) argued that various aspects of a system for guiding actions of healthcare workers were technical, but without success. Board 3.5.05 held that neither helping healthcare workers become accustomed to change, giving them more flexibility, relieving them from having to remember tasks nor presenting a list of options in a more efficient order were technical.

The same Board rejected the application in T 3119/19 (Unacceptable values/ROCHE). It was argued that informing the patient that a sample value fell outside an acceptable range provided guidance that would, in the long term, prevent waste and thus had a technical effect. However the Board held this argument “is an example of a broken technical chain: the alleged technical effect of reducing wastage of test strips is achieved through a chain starting with information provided to the patient which is then broken by the patient’s mental activities. The alleged technical effect cannot be achieved independently of the cognitive content of the information presented to the patient and the patient’s subsequent mental activities.”

Board 3.5.01 in T 1900/18 (Ingredient-based product recommendation/SOUTHAM) rejected claims to a system for recommending wellness products on several grounds including that it did not solve a technical problem and was not inventive “because, at the level of generality claimed, it merely automates standard medical practice”. A further objection that the invention did not provide an advantage over its whole scope is discussed above.

Technical and Non-technical

Boards of Appeal have long declined to give a closed definition of what is and is not technical, in many cases for fear that such a definition would be overtaken by newly developed technology. Board 3.5.01 again refused to do so in T 0550/14 (Catastrophe relief/SWISS RE) where the appellant argued that the lack of established criteria for Examining Divisions to use to show that a feature is non-technical hindered the presentation of counter arguments. The Board did however issue some useful guidance to the Divisions as to how to structure a debate on technicality:

“Thus an objection from the division should probably start with a prima facie assertion that the feature in question is non-technical, perhaps because it is in one of the exclusions listed in Article 52(2) EPC, or a related or analogous field. If this is uncontested then this would be enough. However the Board considers that it is then up to the appellant to provide arguments why there is a technical effect or that some technical considerations are involved. The division should consider these arguments and give reasons why they are not convincing.”

Notional business person

The notional business person introduced in T 1463/11 (Universal merchant platform / CardinalCommerce) has since then had frequent appearances in decisions relating to implementation of non-technical methods, to help separate technical and non-technical features. Like Barbie(RTM), the notional business person has had many careers, including, in 2022:

- an insurance expert in cooperation with airline companies to design a system for automating insurance payments in case of airport closures (T 0288/19 and several other appeals by SwissRe)

- a ‘“notional psychologist” (or better “notional pedagogue”)’ for an invention relating to a training method using computerized avatars (T 0344/19)

- a TV station manager proposing the inclusion of additional information, such as betting odds, in a live broadcast (T 1117/19 (Lückenfüller bei TV-Live-Ereignissen/NOVOMATIC))

- a real estate agent calculating the value of property (T 2295/18 (Evaluating real estate/TECNOCASA))

Board 3.5.01 in T 0909/14 (Web service without upfront storage/MICROSOFT) expands on the Cardinal Commerce approach, saying:

“the test used in deciding on technicality of a feature is whether the notional business person could have come up with it. This boils down to determining whether there would have been at least one way to devise it without technical considerations. If so, it does not have technical character and may form part of the requirement specification regardless of what alternative ways of arriving at it were disclosed in the application or were conceivable.” (emphasis added)

In a sense this is analogous to the position on inventive step that if it is obvious to get to the invention from one starting point it lacks inventive step even if it would not be obvious given a different starting point.

The same Board (T 2626/18 (Insurance risk prediction/SWISS RE)) rejected the possibility of a third category of person in the team:

“With its argument that neither the business person nor the technical person could have come up with the claimed features, the appellant seems to thereby allege that only an imaginary third person could have devised concepts enabling the invention to be implemented on a computer system. The appellant apparently considers that the fact that such a third person is needed supports inventive step. However, the Board notes that, when assessing inventive step in the field of computer-implemented business-related inventions following the COMVIK approach and the corresponding case law, there is no room for such a third expert. When analysing the features of a claim and answering the question of whether they provide a technical contribution, each feature has to be judged to be either a contribution of the technical expert or a contribution of the non-technical business person in order to conclude whether there is an inventive technical contribution.”

Business Methods

T 0658/18 (Aggregated soft card/MASTERCARD) is an interesting case of an application proceeding to grant as an inventive technical implementation of a business method. The underlying business method was to link a credit or payment card to a loyalty card, so that loyalty points are earned whenever the payment card is used, as an “aggregated soft card” on a mobile device. Although the Examining Division had considered most of the features of the claims to be obvious implementation of the business idea, the Board held that features relating to use of a database and communicating between servers where technical and not obvious. The case was remitted for a further search and at the time of writing a proposal for grant has issued. This is a case where it seems to have helped that some aspects of the business case where known and that other ways of implementing the business idea were conceivable, even more obvious, based on the prior art. These circumstances make it easier to argue that the invention is the technical implementation of the business idea, not the business idea itself.

A case where the Board disagreed with the Examining Division’s assessment of technicality was T 1158/17 (Routing electronic message/ESCHER GROUP). This related to a secure email system and the Examining Division had drawn an analogy with a traditional postal system as the basis of its objection of lack of inventive step; the technical components were claimed in general terms and merely the obvious implementation of the traditional postal system. In overturning the objection, the Board made several interesting points:

- “provision of … computers and/or programs in order to route an electronic message from one location to another involves considerations which go beyond what the business person … is aware of”

- “claim components … defined in functional terms at a high level of abstraction, … alone is not sufficient to negate the technical considerations involved in providing those components.”

- “a similarity to a business or administrative solution is not a sufficient reason for denying a technical contribution of a claim feature applied in a technical context and involving technical considerations. Put another way, technical considerations in the technical context cannot be negated merely on the basis of a non-technical analogy”

- “lack of technical detail does not remove … the technical contribution of routing electronic messages and ensuring their integrity in a novel manner. The questions as to which hardware should be used and what particular programming techniques should be employed were not the focus of the invention and the application legitimately relies in this respect on the skilled person’s common general knowledge”

T 1984/18 (Prüfung von Zahlungsbelegen/EFSTA) related to the electronic storage of payment receipts in a tamper-proof way and provides an interesting contrast between features considered to be of a business nature (storage and examination of accounting data) and those which are technical (use of encryption, access codes to a data store and the creation of operating data). Furthermore, Board 3.5.01 criticised the decision under appeal because it “merely established that the individual features are obvious in themselves, without considering whether, for example, a functional interaction of the features achieves a combinatorial technical effect.” They also commented that “underlying idea may be of a business nature, but the concrete implementation is technical in nature and enables a simple and safe verification for the customer.”

Some other business methods and aims that have addressed by Boards include:

- “automatic charging of the final amount to the customer when they leave the outlet represents the non-technical business aim”, compared to prior art that merely alerted staff T 0351/19

- “restricting the redemption of a voucher to a particular machine is not a technical problem, and providing an identifier, such as a name or a number, for identifying the machine is an administrative matter. Thus, it follows that the non-technical requirement specification dictates that the voucher should be associated with a vending machine identifier, and this identifier should be compared with the identifier of a vending machine to which the voucher is presented.” T 0800/20 (Restricted voucher redemption/MICROTRONIC)

- “it is part of the non-technical requirement specification to keep keys (be it analog or electronic keys) away from people one does not trust. This does not require technical considerations of a technically skilled person. The Board does not consider this to be a technical difference, but to be an administrative consideration within the sphere of a business person when contemplating a secure tender process. It is not regarded as a technical innovation, but a natural choice for the bidders to use individual keys, keep the keys back as long as possible and furnish them as late as possible. And even if this was considered technical, it would, in the Board’s view, be obvious to do so.” T 1026/17 (Securing a tendering system/KOHLI)

- “Defining and using rules concerning business aspects for different customers or types of customer is a business decision”, in contrast with rules based on the size of a print job T 1567/19 (Workflow generation in a print shop/RICOH)

- “adjusting any difference between an accounted total amount and the amount of cash picked up by an armored car.” T 1607/18

- “choice of a delivery location can be based on non-technical business considerations and constraints or preferences of the recipient (such as a preference for a specific location for picking up the packet, e.g. a locker near the recipient’s residence or the workplace)” T 1909/19 (Confirming identity at locker bank/UPC)

- customisation of products, specifically sportswear T 2027/17 (Offering a customized collection of products/ADIDAS AG)

Presentation of information

Objections that inventions are presentations of information are common and the test that to be patentable an invention of this type must credibly assist the user in performing a technical task by means of a continued and guided human-machine interaction is well established. In T 1743/19 (Possible next actions/CAREFUSION303) the test was failed because selecting from a menu is not a technical task.

There is old case law (T 0115/85 (Computer-related invention/IBM) of 5/9/1988) holding that automatically indicating the internal status of a machine is technical, but Board 3.5.03 in T 2948/19 (Operation status index divided into regions/SYSMEX) confirm this only applies if it allows the user “to interact with the system to enable its proper functioning” and “assists the user in performing a technical task by means of a continued and guided human-machine interaction process.” In the particular case, the information provided – combined error rates of groups of laboratories – did not provide enough information to enable the user to take any useful action.

A case where the test was passed was T 3117/19, but only in an auxiliary request. The invention concerned control of a gear cutting machine and the crucial limitation solved the technical problem of “making or simplifying the operation of the gear cutting machine in a more user-friendly manner” so that an additional input option was reached more quickly.

Methods of presenting information can also be rejected if any improvement is only a matter of personal preference, as in T 2830/19 (A method for displaying and navigating calendar events/SEUTHE). The invention here proposed that the user “walk into” a display of calendar events but the Board considered this to be “a different presentation of calendar events … [which] may be preferred by some users, but this depends on personal preference”.

Programming

Programming has been held by Boards to be a cognitive process that is not technical and so saving programmers effort is not a technical problem. This was the ground of refusal in by Board 3.5.06 in T 1105/17 (Compiling programming language constructs/ORACLE). This was especially the case since the invention sought to enable the programmer to write “less verbose” source code.

Similarly, Board 3.5.01 held in T 2021/17 (Intelligent agents/UNIVERSITY of STRATHCLYDE) that “the internal structure of a computer program, for example the particular configuration of software modules, objects, or, indeed, “agents”, does not provide a further technical effect”. Furthermore, there was “no definition for what an agent is in terms of technical properties either in the application or even generally in the art (see D1, II.A). Thus, the agents in claim 1 cannot be distinguished from software modules suitable for implementing the desired functions”.

In T 0698/19 Board 3.4.03 cites earlier case law that an algorithm is not inherently technical but can be if it is designed with technical considerations in mind. They remark though that to rely on this route to patentability:

“Disclosure as to how the algorithm is implemented in practice must be provided in order to give evidence that the algorithm has any proved further technical effect with respect to known algorithms and that it provides an improvement over the prior art. The present invention has the object to provide a stable system. However, as discussed above, no details are given why the proposed system should be considered to provide better stability than any other system, for example, how and at which level improved stability or accuracy of the algorithm is achieved, which kind of data is used for pattern matching, how historical data is selected, prepared and compared, and which parameters are matched.”

Another appeal by Oracle, T 2804/19 (Data transformation/ORACLE) alleged that an invention obtained speed advantages through the use of regular expressions (a high level syntax for text search patterns that is implemented in many programming languages). However this was not substantiated and Board 3.5.07 observed that “a mere speed comparison with a conceivable reference method that does not use regular expressions is not a suitable criterion for distinguishing between technical and non-technical procedural steps”. They also considered that the use of regular expressions was not based on considerations “relating to the internal functioning of a computer, but on considerations that are purely algorithmic in nature, i.e. relating to computer programs as such. It therefore does not contribute to a technical effect for the purpose of assessing inventive step.”

Games

A decision illustrating several of the above themes related to a “computer implemented method of measuring crew member communication skills”. In T 2689/18 Board 3.4.03 considered overall that “detection of the crew’s behaviour during conversation and the objective ranking thereof” is equivalent to activity carried out by a trainer or supervisor and hence non-technical. Digging into the detail of the claims, “specific prosodic parameters used in the analysis are based on speech utterance and are as such non-technical, because they involve a mixture of administrative, psychological and mental acts, all of which are non-technical”. An alleged increase in objectivity “belongs to the very nature of a computer-implemented method and does not provide anything surprising.” A feature relating to a default length of a time window was argued to provide a better rating but in the Board’s view ‘Given the fact that the obtained rating has no technical meaning …, the Board considers that “a better” or “more accurate” rating has no technical meaning, either, since any interpretation of the rating and its quality is based on non-technical aspects.’

Other non-technical subject matter

Some other examples of features and problems considered non-technical are:

- “Whether a user finds it easy or difficult to follow an exercise is not a technical but a psychological matter. Aerobics is not technical.” (emphasis added) Board 3.5.05 in T 0541/19 (Replaceable musical accompaniment/AKOPIAN)

- Most of T 0872/19 (Concept terms scoring/GOOGLE) relates to advertising, which is well established to be a business method, but makes the interesting point that “not all image classifications solve a technical problem. If a user classifies displayed images via a user interface to have the images arranged according to the user’s viewing preferences, the image classification will, in most cases, not solve a technical problem.”

- “Enhancing immersiveness of a virtual environment by mimicking realistic illumination aims at a subjective experience of a viewer.” T 0971/18

- “The purpose of generating a more appropriate animation which more reliably reflects and emphasises emotions or the content, meaning and intentions of the sender of the text in view of the relationship between the sender and the receiver, is not a technical purpose.” T 1008/19 (Generating animation based on text and user information/SAMSUNG)

- “The idea of taking into account the exophoric, endophoric, or anaphoric terms for disambiguation is purely linguistic.” T 1526/19 (Modifying search results based on context/LENOVO)

- “The fact that specific languages with different reading directions are to be supported is a non-technical requirement. “ T 1601/19 (Maintaining view location during rendering/NOKIA)

- “an authenticity metric value for web elements” – essentially websites are ranked according to how closely they are linked to certain “official” sites T 1639/18 (Content ranking based on authenticity metric/DISNEY ENTERPRISES)

- “a policy for selecting [devices] from which the user wishes to get content for publication to his social network account” T 1847/18 (Transferring content stored on remote terminals/TENCENT TECHNOLOGY)

- “allowing the user to state their preferences on which segments of a programme should be recorded based on the type of programme is non-technical because it is essentially based on commercial and psychological considerations, i.e. on making a product more attractive to the user and in creating an effect in the user’s mind” T 2386/17

- “computation and comparison of the “defense levels” and the “value” of the confidential information are non-technical. The three parameters used to calculate the security levels (the cost of tools, the hourly wage of an engineer and the time required for analysis) are not technical, and no criteria are disclosed for computing the value of confidential information.” T 2562/17 (Electronic terminal/PANASONIC)

Technical

Just a couple of cases make useful comments on technical subject matter. In T 0929/18 (Mobile location data sharing/BLACKBERRY) the Examining Division considered that the “peer-to-peer” data sharing group was administrative in nature and its implementation was insignificant technical detail. However, the appellant was able to argue that the peer-to-peer sharing was different than known arrangements and was part of “an electronic communication architecture that cannot be dissected into non-technical and technical parts.” Although the Board apparently still had doubts on inventive step, the case was remitted for a search since to do otherwise “would be to put the cart before the horse by putting the substantive examination before the search”.

In T 1108/20 (Closed-circuit e-commerce entity for services and products/ELBEX) provision of additional computing resources – a CPU and memory – in a “closed circuit e-commerce entity” had the “technical effect of supporting a large number of kiosks without overwhelming the server.” Although aspects of the invention were non-technical, appropriate location of computing resources is a technical problem.

Inventive step

Automation

Mere automation of a known manual process has long been considered by the Boards to be non-inventive, but an interesting argument was made in T 1484/20 (Suggested order generator/SYSMEX): that a partial automation of a method might be inventive. However, Board 3.5.05 did not accept this, commenting that: “the problems identified by the appellant in a fully automated method (i.e. lack of control, inaccuracy in special circumstances) are obvious disadvantages of full automation, and the suggested solution (user intervention via a GUI) is obvious in view of the trade-off between the advantages and disadvantages of different degrees of automation.”

Bonus effects

Technical advantages have frequently been discounted by Boards as inevitable bonus effects of non-technical features that don’t confer technical character. Examples include T 1636/18 (Estimating departure time/QUALCOMM) in which estimates of when a user of a calendar system should set off to get to a meeting were not calculated if the user was close to the meeting location. This was said to save energy, but Board 3.5.01 considered it an inevitable consequence of the decision not to generate alerts as a matter of user preference.

The same Board in T 1983/18 (Recommendation of applications/BAIDU) considered a reduction of network traffic due to alleged better recommendations of applications to a user to be a mere bonus. Again in T 1988/20 (Image browser/APPLE) a reduction in user burden due to clustering of photographs was the inevitable result of implementation of a non-technical scheme.

ChatGPT

With all of the publicity about ChatGPT, the thought occurred as to whether it could save effort in writing this summary. The prompt “what are recent interesting decisions by EPO Boards of Appeal”, elicited the response:

The European Patent Office (EPO) has a system of appeal for parties who wish to challenge decisions made by the EPO’s examining and opposition divisions. These appeals are heard by the EPO’s Boards of Appeal, which are independent bodies that review the legal and technical aspects of the case and issue a decision.

There have been several recent decisions by the EPO Boards of Appeal that may be of interest. Some examples include:

- T 1227/05, “Computer-implemented simulation of shared control of a vehicle” (Decision issued on September 10, 2020): This case involved a patent application related to a system for simulating the shared control of a vehicle, such as a car or aircraft. The Board of Appeal found that the claimed invention was not eligible for patent protection because it did not involve an inventive step.

- T 2557/19, “Computer-implemented simulation of a mathematical model” (Decision issued on December 17, 2020): This case involved a patent application related to a system for simulating a mathematical model on a computer. The Board of Appeal found that the claimed invention was not eligible for patent protection because it did not involve an inventive step.

- T 2275/19, “Computer-implemented simulation of a fluid flow” (Decision issued on January 21, 2021): This case involved a patent application related to a system for simulating the flow of a fluid, such as water or air, on a computer. The Board of Appeal found that the claimed invention was eligible for patent protection because it involved an inventive step and was susceptible to industrial application.

These are just a few examples of recent decisions by the EPO Boards of Appeal. There have been many other decisions on a wide range of technical subjects, and it is not possible to provide a comprehensive overview in this forum. If you have specific questions about a particular case or decision, it may be helpful to consult with a patent attorney or other qualified professional.

It is quite astonishing that ChatGPT can make up apparently reasonable case references, but “make up” is the operative term. Decision T 1227/05 is in fact the well-known Circuit simulation I/Infineon Technologies decision of 13.12.2006 which was actually granted, whilst there are no cases T 2557/19 and T 2275/19.