The Battle Against Look-a-Likes Part 2 – Aldi Fails to Light up UK Court of Appeal

In early April last year, we reported on the decision of the UK High Court in design infringement proceedings brought by the retailer M&S against fellow supermarket Aldi, relating to a gin bottle. Our original report is here.

Aldi appealed to the UK Court of Appeal, who gave its decision on 27 February 2024. The Appeal decision can be found here.

The decision is important, being the first decision by the Court of Appeal on a design matter since the UK left the EU, and as it has clarified several important issues which may feed through to filing strategy for designers in future.

The earlier decision

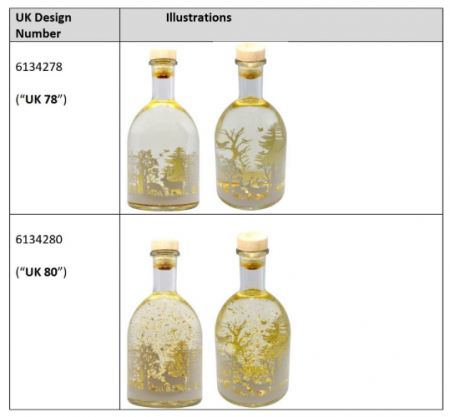

The original case involved flavoured gin liqueurs offered by Aldi in light-up bottles containing gold flakes which, when shaken, created an effect reminiscent of a snow globe:

The products were found to infringe the following four M&S Registered Designs which had the same integrated light feature and snow globe effect:

The first instance decision was seen as an important example of how registered design rights can be used to prevent look-a-like products in the marketplace, where other claims, based on registered trade marks and the law of passing off, often fail.

Aldi’s appeal

Aldi appealed on several grounds. We discuss the main ones below:

Interpretation of the registered designs

Aldi appealed the first instance decision on the ground that the judge had misinterpreted some of the features of the M&S Registered Designs, specifically that two of the designs showed a clear bottle against a dark background with an integrated light feature at the base of the bottle, not present in the other two.

Lord Justice Arnold (Arnold LJ) reconsidered this, finding that all designs showed the integrated light feature, and that the judge was correct to conclude that two of the designs were clear bottles on a dark background. In reaching these conclusions, Arnold LJ took support from a) an inspection of the M&S products in the market, and b) that the indication of product (referred to as description in the earlier judgement) could be relied upon to resolve any ambiguities in the images, and thus in the interpretation of the design.

In relation to a), the judge had found that products manufactured by the proprietor to which the design is applied were “irrelevant to interpretation of the design”. Arnold LJ found this was incorrect, citing prior case law which holds that physical embodiments of the designs can be considered “to confirm the conclusions already drawn” [from reviewing the images of the Registered Design].

Second, Arnold LJ considered the effect of the “Indication of Product”, “Light Up Gin Bottle”, as used in the M&S Registered designs. In our comment on the first instance decision, we noted how the judge had considered whether a description (an optional provision under Rule 4(5) of the Design Rules) can be relied upon to resolve an ambiguity of the interpretation of the design by looking at the images alone. We noted that it appeared that the judge had been confused by what the UK IPO online register showed as the “description”, which in fact was the Indication of Product.

It appears that the UK IPO also took note, as in late April 2023 they changed (for all designs on the Register) the heading “Description” on the online record to its correct title, “Indication of Product”. Arnold J was therefore able to answer a slightly different question to that considered by the judge, namely “can the indication [of product] be relied upon to resolve an ambiguity as to what is shown in the images, and in that sense to assist in the interpretation of the design” [notwithstanding that the Design Rules state that the indication of product does not affect the scope of protection conferred by registration of the design].

Arnold LJ concluded that it can be relied upon in this way, pointing to the example that if reviewing the M&S Designs on the register, the indication of product “Light Up Gin Bottle” provides an unambiguous answer to the question of whether the designs include an integrated light feature (as had been missed by the judge for two of the designs).

Design corpus relevant to assessment of infringement

Arnold LJ then went on to consider the judge’s assessment on whether the Aldi designs infringe those of M&S. In doing so, he considered the most interesting ground of appeal in the case, namely, whether a designer’s own disclosures within the grace period (of the same or related designs) form part of the design corpus, which is then relevant to the assessment of infringement.

Put simply, in UK (and indeed EU) Law, designs that are new (no identical design or designs that differ only in immaterial details made available to the public (disclosed) before the relevant date), and which have individual character (its overall impression differs from any other design disclosed before the relevant date), are deemed to be valid (unless barred by other provisions not relating to the novelty of the design). Designs disclosed by the designer or its successor in title in the 12 months before the relevant date (“the grace period”) do not count as invalidating disclosures. The grace period therefore allows a designer to test a design in the market before deciding if is worth the additional protection afforded by a design registration. The relevant date for these purposes is the filing date or, if there is one, the priority date.

In an assessment of infringement, the key test is whether the later design will produce a different overall impression on the informed user than that of the registered design. In determining the overall impression, the informed user will have in mind any earlier designs that have been made available to the public. Where an earlier design is markedly different to what has gone before, its overall impression on the informed user will be greater, and the room for differences which do not create a substantially different overall impression greater still. Thus a strikingly new product has a wider scope of protection that one that is only incrementally different from earlier designs (the prior art), but which may still have enough individual character to be validly registered. The judge found that any disclosures by the designer within the grace period would not form part of the design corpus, and thus no consideration of whether these could narrow the scope of the M&S Registered designs was necessary.

Aldi appealed, first arguing that the grace period was only relevant to the issue of validity, not infringement. Arnold LJ dismissed this, pointing out that if this were the case, the scope of a registered design could potentially be reduced to virtually nil. Arnold LJ then considered what iterations of a design would be captured by the grace period, and what would form part of the design corpus. At trial, the judge reasoned that the European Legislature that allowed for the grace period will have had three possible intentions:

- the designer must register all possible iterations [of the designs it had disclosed in the grace period];

- the grace period extends to the design as well as designs of the same overall impression (thus excluding close iterations from the design corpus); or

- any disclosure, of any design, by the designer in the grace period does not count as a prior invalidating disclosure (as found by the judge).

Aldi appealed on the basis that 1. would be correct. Arnold LJ decided 2 must be correct, 1 would be too narrow, 3 too broad. The correct interpretation must be that the disclosures by the designer of designs of the same overall impression would be captured (and thus by excluded from the design corpus), finding that:

“On the second interpretation the designer will be fully protected with respect to both validity and infringement if all the variants create the same overall impression. As leading counsel for Aldi pointed out, however, the grace period is a limited exception to the proposition that the overall impression created by the registered design should be assessed as at the filing date or (subject to grounds 3 and 4) the priority date. As such, it should not be extended beyond its purpose. If designers test market a number of distinct designs, but only decide to register one, then they must accept the risk that the other designs may in some cases affect the scope of protection of the registered design.”

The relevant date

Aldi’s final ground of appeal related to the date the assessment for infringement, and thus the date on which the assessment of the design corpus and scope of the M&S registered design vis a vis the Aldi product, should be made. Aldi argued this should be the filing date as it is only from this date that a registered design can be infringed. Whilst the M&S Registered design had a claim to priority, Aldi again argued this was only relevant for the assessment of validity, not infringement, notwithstanding that the assessment of validity will be the priority date (where there is one). Arnold LJ found against Aldi, pointing out that a claim to priority, like the grace period, is relevant to an assessment of validity and infringement as it affects the overall impression of the registered design. This was important as the version of the product originally marketed and sold by M&S was different to the version subsequently registered.

Comment

This decision, the first by the UK Court of Appeal since the UK left the EU, may help inform filing strategy for those looking to register their designs in the UK in future.

First, what is used as the Indication of the Product in a UK design application can affect how the design will be interpreted, at least for those designs where there may be some ambiguity as to what is depicted by reference to the images alone. One has considerable latitude in a UK design application (unlike, for example, in an EU (RCD) design application) in choosing the Indication of Product. If a product includes an unusual design feature (in this case, the integrated light), it will help to include this in the Indication of Product (as M&S had), perhaps also adding the appropriate name from the Locarno classification to ensure the UK IPO classify the design correctly.

Second, the court’s findings in relation to the effect of a designer’s disclosures within the grace period highlight the benefits and risks of relying on it prior to applying to register a design, or designs, for a particular product. In an ideal world, new design applications should be filed prior to any disclosure, in order to allow for the widest possible scope of protection (unaffected by a designer’s own disclosures), and allow for protection in those jurisdictions that do not allow for a grace period, such as China. However, many businesses do not operate in an ideal world, and tend to test market various iterations of its products (and thus designs) before arriving at a final version.

The decision confirms that variations on a design that produce the same overall impression are excluded from the design corpus, such that all disclosed iterations do not need to be registered. However, where the scope of many designs is often narrow, small differences may be enough to create a different overall impression. Therefore where various iterations of a design have been test marketed in the grace period, consideration should be given to filing to register each variation (other than those that differ only in immaterial details) in a multiple design application. Where additional costs per design are low, such a multiple application will provide a bundle of registered rights, each relatively narrow in scope, but which may be enough to capture third party designs that would not otherwise infringe where only a single design has been registered.