Trade Marks in the Metaverse

Earlier this month, a federal jury in the United States found that Hermès’ Birkin trade mark was infringed by the artist Mason Rothschild, creator of a range of digital images depicting faux fur handbags, and associated non-fungible tokens (‘NFTs’), referred to as ‘MetaBirkins’.

The dispute between Hermès and Rothschild has become a high-profile example of the potential for infringement of IP rights by creators and users of the expanding range of virtual platforms known as the ‘Metaverse’.

Brands in the Metaverse

As explained by an article on the Merriam-Webster dictionary’s website, the concept of the metaverse is that of “a highly immersive virtual world where people gather to socialize, play, and work.” At present, there are several metaverses provided by competing platforms including Horizon Worlds, operated by the social networking company Meta (the parent company which operates Facebook and Instagram), and video games such as Roblox and Minecraft.

Metaverse platforms are characterised by the existence of user-created content, including virtual products and even spaces designed to evoke a ‘real-life’ equivalent. These virtual worlds are becoming increasingly ‘branded’, with companies creating spaces dominated by their brand’s imagery and allowing users to view and purchase virtual products.

A high-profile recent example is the launch of Nikeland, accessible via the Roblox platform, visited by over 7 million users in its first five months. Visitors to Nikeland are able to view and ‘try on’ virtual Nike sneakers as well as play branded games to compete for virtual rewards.

What lessons can be learned from the MetaBirkins case?

In the MetaBirkins case, Hermès was able to convince a jury that Rothschild’s range of digital images and NFTs were not solely works of art but instead were sold in a manner that would confuse consumers as to their origin. Rothschild was also held to have been liable for ‘cybersquatting’ through his registration and use of the domain name metabirkins.com.

In particular, the sale of NFTs linked to the digital images appears to have been a determining factor in the jury’s decision to find in favour of Hermès. This could suggest that, in a virtual space where brand imagery is displayed, but virtual goods are not actually being sold, a brand owner may find it more difficult to prove that their trade mark registration covering physical goods has been infringed.

The verdict suggests that brand owners (and particularly larger companies like Hermès who can prove that their trade mark has a reputation) can enforce rights infringed in the metaverse in certain circumstances. It does, however, highlight the risk posed by infringing acts in the metaverse to owners of trade mark registrations that cover physical goods, but not their digital equivalents.

How can brand owners protect themselves?

A trade mark registration covering virtual goods and related software would provide a valuable layer of protection to brand owners concerned by appropriation of their trade marks, particularly on virtual goods designed to replicate a real-life product. This is especially the case for brand owners who may struggle to prove that their trade marks are sufficiently well-known to have enhanced distinctive character by virtue of a reputation.

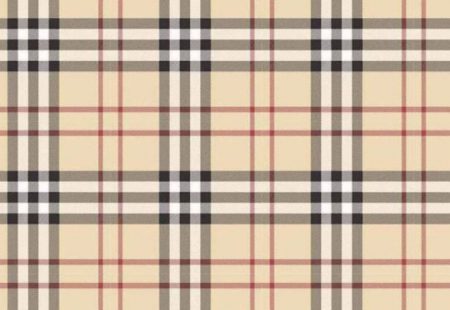

A cautionary tale, however, has arisen from the EU IPO, which recently refused an application by Burberry for a depiction of its famous tartan-check pattern in respect of a variety of virtual goods. The refusal was on the basis that the pattern could be considered a generic surface decoration when applied to virtual clothing or other ‘wearable’ virtual products.

The Examiner observed, in the refusal (based on Article 7(1)(b) EUTMR) that:

“The Office notes that the consumer’s perceptions for real-world goods can be applied to equivalent virtual goods as a key aspect of virtual goods is to emulate core concepts of real-world goods."

The EU IPO’s practice may not deter brand owners from seeking to protect non-traditional trade marks in relation to virtual goods, even if these might be refused protection for their physical equivalents. The metaverse is, after all, a developing concept and consumer expectations of content within it will change over time. Further case law may be needed to establish the extent to which virtual goods are perceived as equivalent to their real-world counterparts by consumers.

Advice on the appropriate level of trade mark protection for virtual products can be obtained by speaking to your usual contact at J A Kemp. For further information on protection of intellectual property rights in the metaverse, read our Insight on patenting metaverse-related inventions here.