CJEU Rules on the Registrability of Shape Trade Marks

The CJEU has delivered its decision on Case C-205/13 Hauck GmbH v Stokke A/S & others regarding the registrability of shapes as trade marks. The case concerns the grounds for refusal or invalidity of a shape trade mark under Article 3(1)(e) of the Trade Marks Directive (2008/95/EC), which provides that a sign shall not be registered as a trade mark or, if registered, shall be liable to be declared invalid, if it consists exclusively of:

The CJEU has delivered its decision on Case C-205/13 Hauck GmbH v Stokke A/S & others regarding the registrability of shapes as trade marks. The case concerns the grounds for refusal or invalidity of a shape trade mark under Article 3(1)(e) of the Trade Marks Directive (2008/95/EC), which provides that a sign shall not be registered as a trade mark or, if registered, shall be liable to be declared invalid, if it consists exclusively of:

- the shape which results from the nature of the goods themselves;

- the shape of goods which is necessary to obtain a technical result;

- the shape which gives substantial value to the goods.

In relation to subsection (i) of the Article, the CJEU held that a sign consisting of a shape which results from the nature of the goods must, in principle, be denied registration where the shape discloses one or more essential characteristics which are inherent to the generic function or functions of that product. Reserving such characteristics to a single economic operator would make it difficult for competing undertakings to give their goods a shape which would be suited to the use for which those goods are intended, these being the essential characteristics which consumers will be looking for in the products of competitors. In relation to subsection (iii), the CJEU held that the shape need not constitute the main or predominant value of the goods in order to be objectionable under that subsection, nor is the subsection limited to shapes having purely artistic or ornamental value. The shape need only give substantial value to the goods, and this may be the case even where the product exhibits several characteristics each of which may give that product substantial value.

Background

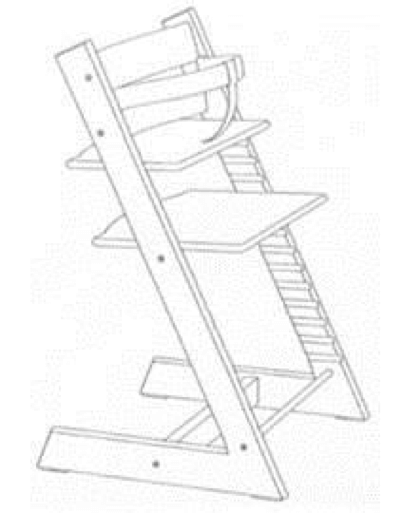

The case involves the well-known Tripp Trapp high chair, first launched by Stokke in 1972. In 1998, Stokke applied for a Benelux trade mark registration for the shape of the Tripp Trapp chair as shown below.

Registration was granted for “chairs, especially high chairs for children”.

Hauck manufactured and sold its own children’s high chairs, including two chairs named “Alpha” and “Beta”. Stokke brought an action in the Netherlands claiming that Hauck’s manufacturing and marketing of the “Alpha” and “Beta” chairs infringed Stokke’s Benelux trade mark registration. In response, Hauck successfully counterclaimed for a declaration that Stokke’s trade mark registration was invalid. In an appeal before the Supreme Court of the Netherlands, the Court referred several questions to the CJEU regarding the interpretation of Article 3(1)(e).

Shape Resulting from the Nature of the Goods

The referring court’s first question asked whether subsection (i) should be interpreted as applying only to a sign which consists exclusively of a shape which is indispensable to the function of the goods in question, or whether it may also apply to a shape with one or more characteristics which are essential to the function of that product and which consumers may look for in competitors’ goods.

The CJEU outlined the rationale behind the grounds for refusal listed in Article 3(1)(e), namely to prevent trade marks being used to create a monopoly over functional characteristics or to extend indefinitely the life of otherwise finite IP rights, such as designs.

That being so, the CJEU held that if subsection (i) were limited to signs which consist exclusively of shapes which are indispensable to the function of the goods in question, this would effectively exclude only “natural” products which have no substitute, and “regulated” products whose shape is prescribed by law, which would in any event be prevented from registration by virtue of their lack of distinctive character, thus the underlying objective of the grounds for refusal would not be met.

Consequently, the CJEU concluded that subsection (i) extends to shapes of products with one or more essential characteristics which are inherent to the generic function or functions of the product, and which consumers may look for in the products of competitors, though the Court was keen to emphasise that subsection (i) cannot apply where the trade mark relates to a shape of goods in which another element, such as a decorative or imaginative element, which is not inherent to the generic function of the goods, plays an important or essential role.

It is interesting to note the CJEU’s comments regarding the process for assessing the “essential characteristics” of the sign, namely that the assessment may be based either on the overall impression produced by the sign or on an examination of each of the components of the sign in turn. This suggests that a sign may be assessed differently within the context of Article 3(1)(e) than in the context of Article 3(1)(b) (distinctiveness) and Articles 4 and 5 (conflicts between identical/similar trade marks), where it is the overall impression of the mark(s) that must be assessed.

Shapes giving Substantial Value to the Goods

The second question referred by the Netherlands Court was whether subsection (iii) should be interpreted as applying to a sign which consists exclusively of the shape of a product with several characteristics, each of which may give that product substantial value (such as, in the case of children’s high chairs, safety, comfort and reliability), or if the shape of the product must be considered the main or predominant value in comparison with such other values. The referring Court also asked if “substantial value” refers to the motive(s) underlying the relevant public’s decision to purchase and, if so, what proportion of public opinion is sufficient to deem the value “substantial”.

The CJEU noted that the fact that the shape of a product is regarded as giving substantial value to the product does not mean that other characteristics may not also give the product substantial value. Indeed, limiting the application of subsection (iii) to products having only artistic or ornamental value would mean that products having essential functional characteristics as well as significant aesthetic value would not be caught by the ground for refusal.

The CJEU therefore concluded that subsection (iii) may apply to shapes of products with several characteristics, each of which may give that product substantial value.

In relation to the public perception of the sign under Article 3(1)(e), the CJEU found that this is not a decisive element when applying the ground for refusal under subsection (iii), but may be a relevant criterion of assessment. Other assessment criteria may also be taken into account, such as the nature of the category of the goods, the artistic value of the shape in question and the dissimilarity from other shapes in common use on the market.

May the Article 3(1)(e) Grounds for Refusal be Applied in Combination?

The referring Court’s third question asked whether the grounds for refusal set out in Article 3(1)(e) may be applied in combination. The CJEU held that the three grounds for refusal set out in Article 3(1)(e) operate independently of one another and cannot be applied in combination. If any of the three grounds is satisfied, the sign in question cannot be registered. It is irrelevant if more than one of the grounds applies, but registration should not be refused under Article 3(1)(e) unless at least one of the grounds is fully satisfied.

Comment

The registration of shape marks has always presented difficulties for brand owners, and the decision of the CJEU will not come as a surprise to many. It serves as a warning to those brand owners who have been able to register the shape of their product as a trade mark in the EU to consider carefully the validity of their registration before seeking to rely upon it in any contentious proceedings.

It will now be for the Supreme Court of the Netherlands to apply the decision to the particular facts of the Tripp Trapp case.