What Ancient Persia Can Teach us About Energy Efficiency in Buildings

There is no doubt that the Earth is getting warmer. According to the 2022 Global Climate Report from NOAA’s National Centers for Environmental Information, 2022 was the sixth warmest year since global records began in 1880 at 0.86°C above the 20th century average of 13.9°C.

The global temperatures of 2022 were not just a fluke, the last nine years (2014-2022) rank as the nine warmest years in the 143-year record. These numbers are significant because as temperatures rise and populations continue to grow (the Earth passed the 8 billion people milestone towards the end of 2022), the use of electricity-intensive air conditioners and fans becomes progressively more common. They are no longer a luxury but a necessity to live and work in many countries.

A report by the International Energy Agency (IEA) from 2018 states that the usage of air conditioners or fans to stay cool was responsible for around 10% of all global electricity consumption. The IEA goes on to predict that the global share of electricity demand for space cooling will rise to 37% in 2050, consuming as much electricity as all of China and India at the time the report was written. All this at a time when there is a concerted focus, for the very same reasons, on limiting or reducing global energy consumption.

One way to address this problem is to ensure that new buildings are designed with sustainability in mind. Sustainable construction is becoming ever more relevant, with various government initiatives and regulations coming into effect to encourage green building practices, such as the UK’s Green Homes Grant. Part of this environmentally-focused design is in implementing alternative methods for space cooling without having to make use of electricity-hungry air conditioners.

As a result, a technology that is over 3,000 years old is becoming an increasingly hot topic in the construction sector.

The ancient Persian way of keeping cool

Long before electric air conditioners existed, ancient people discovered a way of naturally cooling their buildings to deal with the hot climate they lived in. They made use of structures called windcatchers, which are towers that rise high up above the surrounding buildings. They were often rectangular with vented openings in the upper walls. These windcatchers were designed to, as the name suggests, catch the cool wind and funnel it down into the interior of the building below. This air sometimes also passed over pools of water in the base of the windcatcher to make use of further evaporative cooling effects. Eventually, as the air in the building warmed it would rise and leave the building through another tower or opening in the walls. Even in the absence of wind the windcatcher acts as a solar chimney, providing a place for the hot air to rise and escape, with the resulting pressure difference pulling fresh air in through the lower windows. The height, size, and shape of the towers, and the numbers and direction of the openings in the walls were all carefully considered to optimise the cooling potential of the windcatcher. These decisions in combination with the layout of the interior of the dwelling below played an important part in the design process.

Windcatchers: a topic of growing interest

Research into windcatchers has rapidly increased in the last decade, with 134 scientific journal articles in connection with the topic published in the 2010s, compared to just 8 in the 1990s. With the recent advances in computing power and the relative accessibility of modern computational fluid dynamics techniques, the research has evolved into the development of new innovative windcatcher systems. These may bear little visual resemblance to the traditional structures of the past but the technology is remarkably similar.

Some examples of these new systems can now already be seen in many Western countries. Atop the Senedd building in Cardiff sits the world’s largest free rotating wind driven cowl that rotates with the wind to ventilate the debating chamber below. Then there is, the Zénith concert venue in Saint-Étienne, which has a distinctive cantilevered roof structure, that was designed with an extremely wide aluminium windcatcher scoop, as a result of detailed aerodynamic studies.

However, it is in everyday buildings where the biggest difference can be made by adopting these technologies. There are mass-produced designs which modernise the windcatcher by integrating a solar powered fan to improve circulation, heat exchangers to recover heat from the outgoing air, louvres to prevent the ingress of dust or precipitation, and dampers to open and close the windcatcher on a schedule or in response to climate or user inputs. These modern high-tech devices are increasingly being employed in residential buildings as the “Passive House” concept gains popularity.

"Ventilation arrangements"

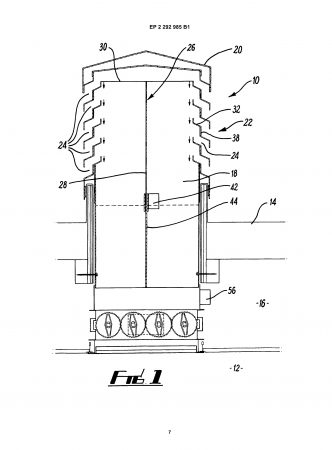

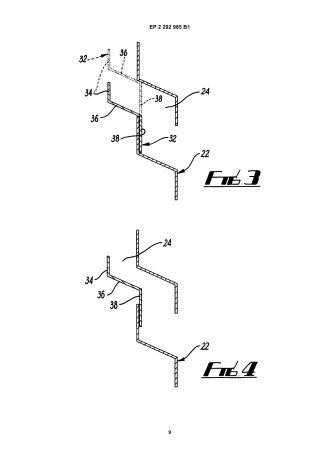

As a result, we can expect to see an increasing number of patents in the coming years for environmentally-friendly solutions to problems like space cooling. For example, a patent for a new design of windcatcher was granted in 2019 (EP 2292985) which comprises a novel arrangement of closable louvres. Closable louvres allow for a user to control the amount of airflow and prevent the ingress of snow or rain during inclement weather while still providing some ventilation. However, partial closing of the vents by merely blocking the vents can interrupt the flow of air over the louvres. EP 2292985 solves this problem by providing novel inner and outer louvre arrangements which slide relative to each other to partially close the vents while providing ducted channels for the air flow. This arrangement has been found to allow more user control over the desired ventilation levels.

Next time you are out and about, look up and see if you can spot it in the wild, because while the original technology may be ancient it has never been more relevant than today.

J A Kemp has extensive expertise in advising on inventions in the general field of mechanical engineering and building design, particularly in relation to energy-saving and automation. See our Green Energy and Climate-tech specialism to find out more.